On September 8, 2022 on the website of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) the opinion of Advocate General Rantos in Case C-707/20, Gallaher Limited versus the Commissioners for Her Majesty’s Revenue & Customs (ECLI:EU:C:2022:654), was published.

Introduction

This request for a preliminary ruling from the Upper Tribunal (Tax and Chancery Chamber) (United Kingdom), concerns the interpretation of Articles 49, 63 and 64 TFEU.

The request has been made in proceedings between Gallaher Limited (‘GL’), a company resident for tax purposes in the United Kingdom, and the Commissioners for Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (United Kingdom) (‘the tax authorities’) concerning whether GL is subject to a tax charge, with no right to defer payment of the tax, in respect of two transactions involving the disposal of assets to companies not resident for tax purposes in the United Kingdom which are part of the same group of companies. More precisely, those transactions consisted, first, of a disposal of intellectual property rights relating to tobacco brands to a sister company of GL, resident for tax purposes in Switzerland (‘the 2011 disposal’) and, second, of a disposal of shares in a subsidiary of GL to its intermediate parent company, resident in the Netherlands (‘the 2014 disposal’).

In the dispute in the main proceedings, GL, in respect of which the tax authorities adopted certain decisions determining the amount of chargeable gains and taxable profits accrued in the context of those two disposals, claims, in essence, that there is a difference in tax treatment by comparison with transfers between members of a group of companies having their residence or their permanent establishment in the United Kingdom, which benefit from an exemption from corporation tax. In accordance with the ‘group transfer rules’ applicable in the United Kingdom, if those assets had been transferred to a parent company or sister company resident for tax purposes in the United Kingdom (or not resident in the United Kingdom but carrying on trade there via a permanent establishment), the tax charge at issue in the main proceedings would not have arisen, as those disposals are considered to be tax neutral.

The question that arises is therefore whether, in the context of those two disposals, the fact of being chargeable to tax without being entitled to defer payment of the tax is compatible with EU law and, more specifically, with the freedom of establishment provided for in Article 49 TFEU (as regards both disposals) and with the right to the free movement of capital referred to in Article 63 TFEU (as regards the 2011 disposal).

In accordance with the Court’s request, this Opinion will focus on the analysis of the third, fifth and sixth questions for a preliminary ruling. Those questions concern, in essence, whether group transfer rules, such as those referred to in the main proceedings, might constitute a restriction on the freedom of establishment in so far as the tax treatment varies according to whether the transaction in question took place between one company and another company of the same group established in the United Kingdom or between one company and another company of the same group established in another Member State. If there is an infringement of EU law, the referring court seeks guidance as regards the nature of the appropriate remedies.

At the end of my analysis, I shall conclude that those rules are compatible with freedom of establishment, in so far as the difference in treatment between national transfers and cross-border transfers of assets for consideration within a group of companies may, in principle, be justified by the need to maintain a balanced allocation of taxing powers, without there being any need to provide for the possibility of deferring payment of the tax in order to ensure the proportionate nature of that restriction.

The dispute in the main proceedings, the questions referred for a preliminary ruling and the procedure before the Court

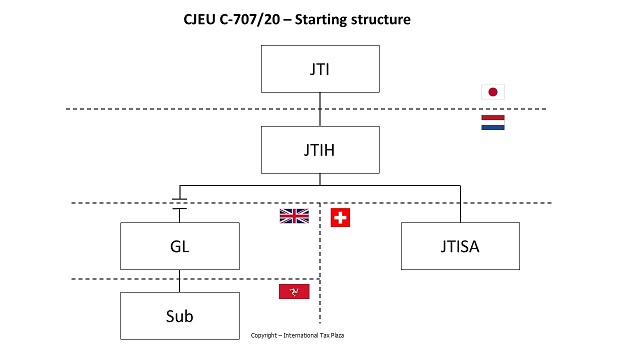

GL is a company resident for tax purposes in the United Kingdom and is a member of the Japan Tobacco Inc. group of companies, a worldwide tobacco group which distributes products in 130 countries throughout the world. The company at the head of the group is a listed company resident for tax purposes in Japan.

It is apparent from the order for reference that the company at the head of the JT group for Europe is JTIH, a company resident in the Netherlands (‘the Netherlands company’) which is GL’s indirect parent company, the family relationship between the Netherlands company and GL being created through four other companies, all established in the United Kingdom.

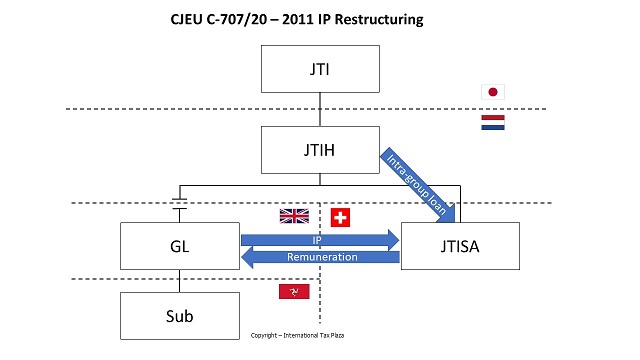

In 2011, GL disposed of intellectual property rights relating to tobacco brands and related assets to a sister company that is a direct subsidiary of the Netherlands company, namely JTISA, a company resident in Switzerland (‘the Swiss company’) (the 2011 disposal). The remuneration received by GL as consideration was paid by the Swiss company, which, for that purpose, had been granted inter-company loans by the Netherlands company for an amount corresponding to the amount of the remuneration.

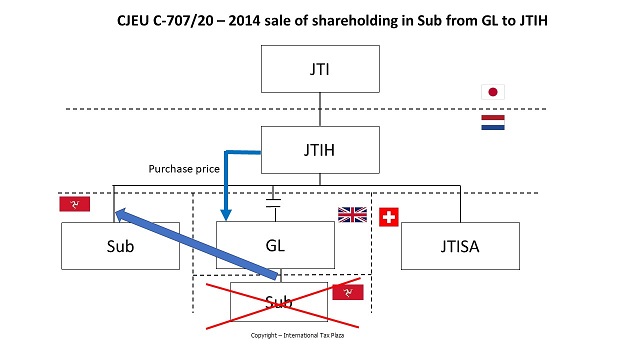

In 2014, GL sold all of the share capital which it held in one of its subsidiaries, a company incorporated on the Isle of Man, to the Netherlands company (the 2014 disposal).

The tax authorities adopted two decisions (partial closure notices) determining the amount of the chargeable gains and profits that accrued to GL in the context of the 2011 and 2014 disposals in the relevant accounting periods. As the assignees were not resident for tax purposes in the United Kingdom, the gains on the assets were the subject of an immediate tax charge and no provision of United Kingdom tax law provided for the deferral of that charge or for payment in instalments.

GL initially lodged two appeals against those decisions before the First-tier Tribunal (Tax Chamber).

In the first place, as regards the appeal relating to the 2011 disposal, GL claimed, first, that the absence of the right to defer payment of the tax charge constituted a restriction on the freedom of establishment of the Netherlands company, second, and in the alternative, that the absence of the right to defer that payment entailed a restriction on the right of the Netherlands company and/or GL to the free movement of capital and, third, that if the United Kingdom, on the basis of a balanced allocation of taxing powers, was authorised to charge the gains realised, the obligation to pay the tax immediately, without the option to defer payment, was disproportionate.

In the second place, as regards the appeal relating to the 2014 disposal, GL claimed, first, that the absence of the right to defer payment of the tax charge constituted a restriction on the right of establishment of the Netherlands company and, second, that if, in principle, the United Kingdom, on the basis of a balanced allocation of taxing powers, was authorised to charge the gains realised, the obligation to pay the tax immediately, without the option to defer payment, was disproportionate. Having lodged that appeal, GL deferred payment of corporation tax pending the determination of the appeal, as it was entitled to do under Section 55 of the TMA 1970.

The First-tier Tribunal (Tax Chamber) concluded that there were good commercial reasons for each disposal, that neither disposal formed part of wholly artificial arrangements that did not reflect economic reality and that neither disposal had the avoidance of tax as its main purpose or one of its main purposes.

It held that EU law had been infringed as regards the appeal relating to the 2014 disposal, but that there had been no infringement as regards the 2011 disposal. It thus allowed the 2014 appeal, but dismissed the 2011 appeal.

In that respect, as regards the appeal relating to the 2011 disposal, the First-tier Tribunal (Tax Chamber) held that there was no restriction on the Netherlands company’s freedom of establishment. With regard to the right to the free movement of capital, it considered that that right could not be relied upon because the legislation at issue applied only to groups consisting of companies under common control.

In the appeal relating to the 2014 disposal, the First-tier Tribunal (Tax Chamber) held that there was a restriction on the Netherlands company’s freedom of establishment, that that company was objectively comparable to a company chargeable to tax in the United Kingdom and that the absence of a right to defer payment of the tax was disproportionate.

GL appealed to the referring court in relation to the 2011 disposal. The tax authorities appealed to the referring court in relation to the 2014 disposal.

The referring court states that the question that arises in the national proceedings is whether, in the context of the 2011 and 2014 disposals, the imposition of a tax charge without the right to defer payment of the tax is compatible with EU law, more specifically, in respect of both disposals, with the freedom of establishment provided for in Article 49 TFEU and, in respect of the 2011 disposal, with the free movement of capital referred to in Article 63 TFEU. The referring court adds that, if the imposition of a tax charge without the right to defer payment of the tax is contrary to EU law, questions then arise as to the appropriate remedy.

In those circumstances, the Upper Tribunal (Tax and Chancery Chamber) decided to stay the proceedings and to refer the following questions to the Court for a preliminary ruling:

‘(1) Whether Article 63 TFEU can be relied upon in relation to domestic legislation such as the group transfer rules, which applies only to groups of companies?

(2) Even if Article 63 TFEU cannot more generally be relied upon in relation to the group transfer rules, can it nonetheless be relied upon:

(a) in relation to movements of capital from a parent company resident in an EU Member State to a Swiss resident subsidiary, where the parent company has 100% shareholdings in both the Swiss resident subsidiary and the UK resident subsidiary on which the tax charge is imposed?

(b) in relation to a movement of capital by a wholly owned subsidiary resident in the United Kingdom to a wholly owned Swiss resident subsidiary of the same parent company resident in an EU Member State, given that the two companies are sister companies and not in a parent-subsidiary relationship?

(3) Whether legislation, such as the group transfer rules, which imposes an immediate tax charge on a transfer of assets from a UK resident company to a sister company which is resident in Switzerland (and does not carry on a trade in the United Kingdom through a permanent establishment), where both of those companies are wholly owned subsidiaries of a common parent company, which is resident in another Member State, in circumstances where such a transfer would be made on a tax-neutral basis if the sister company were also resident in the United Kingdom (or carried on a trade in the United Kingdom through a permanent establishment), constitutes a restriction on the freedom of establishment of the parent company in Article 49 TFEU or, if relevant, a restriction on the freedom to move capital in Article 63 TFEU?

(4) Assuming that Article 63 TFEU can be relied on:

(a) was the transfer of the brands and related assets by GL to [the Swiss company], for a consideration which was intended to reflect the market value of the brands, a movement of capital for the purposes of Article 63 TFEU?

(b) did the movements of capital by [the Netherlands company] to [the Swiss company], its Swiss resident subsidiary, constitute direct investments for the purposes of Article 64 TFEU?

(c) given that Article 64 TFEU only applies to certain types of capital movement, can Article 64 TFEU apply in circumstances where movements of capital can be characterised as both direct investments (which are referred to in Article 64 TFEU) and also as another type of capital movement not referred to in Article 64 TFEU?

(5) If there was a restriction then, it being common ground that the restriction was in principle justified on overriding grounds in the public interest (namely, the need to preserve the balanced allocation of taxing rights), was the restriction necessary and proportionate within the meaning of the case-law of the Court of Justice, in particular in circumstances in which the taxpayer in question has realised proceeds for the disposal of the asset equal to the full market value of the asset?

(6) If there was a breach of the freedom of establishment and/or of the right to free movement of capital:

(a) does EU law require that the domestic legislation be interpreted or disapplied in a manner which provides GL with an option to defer the payment of tax?

(b) if so, does EU law require that the domestic legislation be interpreted or disapplied in a manner which provides GL with an option to defer the payment of tax until the assets are disposed of outside the sub-group of which the company resident in the other Member State is parent (that is, “on a realisation basis”) or is an option to pay tax in instalments (that is, “on an instalment basis”) capable of providing a proportionate remedy?

(c) if, in principle, an option to pay tax by instalments is capable of being a proportionate remedy:

(i) is that only the case if domestic law contained the option at the time of the disposals of assets, or is it compatible with EU law for such an option to be provided by way of remedy after the event (namely for the national court to provide such an option after the event by applying a conforming construction or disapplying the legislation)?

(ii) does EU law require national courts to provide a remedy which interferes with the relevant EU law freedom to the least possible extent, or is it sufficient for the national courts to provide a remedy which, whilst proportionate, departs from the existing national law to the minimum extent possible?

(iii) what period of instalments is necessary? and

(iv) is a remedy involving an instalment plan in which payments fall due prior to the date on which the issues between the parties are finally determined in breach of EU law, that is, must the instalment due dates be prospective?’

Although the United Kingdom left the European Union on 31 January 2020, the Court continues to have jurisdiction to give a ruling on that request.

Written observations have been lodged by GL, the United Kingdom Government and the European Commission.

Conclusion

Advocate General Rantos proposes that the Court should answer the third, fifth and sixth questions referred by the Upper Tribunal (Tax and Chancery Chamber) (United Kingdom) as follows:

(1) Article 49 TFEU must be interpreted as not precluding national legislation relating to group transfer rules which imposes an immediate tax charge on a transfer of assets by a company resident for tax purposes in the United Kingdom to a sister company which is resident for tax purposes in Switzerland (and does not carry on a trade in the United Kingdom through a permanent establishment) in a situation where those companies are both wholly owned subsidiaries of a common parent company which has its tax residence in another Member State, and in circumstances where such a transfer would be made on a tax-neutral basis if the sister company were resident in the United Kingdom (or carried on a trade there through a permanent establishment).

(2) Article 49 TFEU must be interpreted as meaning that a restriction on the right to freedom of establishment resulting from the difference in treatment between national and cross-border transfers of assets for consideration within a group of companies under national legislation which imposes an immediate tax charge on a transfer of assets by a company resident for tax purposes in the United Kingdom may, in principle, be justified by the need to preserve a balanced allocation of taxing powers, without there being any need to provide for the possibility of deferring payment of the charge in order to ensure the proportionate nature of that restriction, where the taxpayer concerned has realised proceeds by way of consideration for the disposal of the asset equal to the full market value of that asset.

Legal framework

The general principles of corporation tax in the United Kingdom

Under Sections 2 and 5 of the Corporation Tax Act 2009 (‘the CTA 2009’) and Section 8 of the Taxation of Chargeable Gains Act 1992 (‘the TCGA 1992’), a company having its tax residence in the United Kingdom is chargeable to corporation tax on all its profits (including chargeable gains) accruing in the relevant accounting period.

Pursuant to Section 5(3) of the CTA 2009, a non-UK-resident company which carries on a trade there through a permanent establishment in the United Kingdom is chargeable to corporation tax on profits attributable to that permanent establishment. Moreover, under Section 10B of the TCGA 1992, such a company is chargeable to corporation tax on chargeable gains accruing to the company on disposal of assets if those assets are situated in the United Kingdom and are used for the purposes of the trade or permanent establishment. Those assets are referred to as ‘chargeable assets’ pursuant to Section 171(1A) of the TCGA 1992.

Under Sections 17 and 18 of the TCGA 1992, the disposal of an asset is deemed to be for consideration equal to market value where the disposal is otherwise than by way of a bargain made at arm’s length or the disposal is made to a connected person.

The rules on transfers within a group of companies in the United Kingdom

Section 171 of the TCGA 1992 and Sections 775 and 776 of the CTA 2009 (together, ‘the group transfer rules’) provide that a disposal of assets between group companies that are chargeable to corporation tax in the United Kingdom must take place on a tax-neutral basis.

More specifically, in accordance with Section 171 of the TCGA 1992, where assets are disposed of by one group company (A) chargeable to tax in the United Kingdom to another group company (B) which is also chargeable to tax in the United Kingdom, that disposal is treated as taking place in consideration for such amount as gives rise to neither a gain nor a loss (so that B is treated as having acquired the assets at the same cost base as that on which A acquired them). However, a tax charge may subsequently arise if the assets are disposed of and give rise to a gain in circumstances in which Section 171 of the TCGA 1992 does not apply (for example, if B disposes of the assets outside the group or disposes of them to a company within the group that is not chargeable to corporation tax in the United Kingdom).

Likewise, if Section 775 of the CTA 2009 applies, then no tax charge (or relief for a loss) arises when intangible fixed assets are transferred from one group company (A) which is chargeable to tax in the United Kingdom to another group company (B) which is also chargeable to tax in the United Kingdom. In fact, B is treated as having held the asset in question at all times that it was held by A and as having acquired it at the same cost base as A. However, a tax charge may arise subsequently, in particular if the assets are disposed of in circumstances where Section 775 of the CTA 2009 does not apply (namely if the disposal is outside the group or to a company which is not chargeable to tax in the United Kingdom).

The applicable double taxation conventions

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland has entered into a large number of treaties and conventions with other territories, typically based on the Model Tax Convention of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). In particular, Article 13(5) of the United Kingdom-Switzerland Double Taxation Convention provides that gains from the alienation of assets, such as those with which the present proceedings are concerned, are to be taxable only in the territory in which the alienator is resident.

The rules on payment of corporation tax in the United Kingdom

In accordance with Section 59D of the Taxes Management Act 1970, in the version applicable to the dispute in the main proceedings (‘the TMA 1970’), corporation tax for an accounting period is payable nine months and one day after the end of that period. Moreover, under Sections 55 and 56 of the TMA 1970, where a decision of the tax authorities (including a partial closure notice) amending a company’s return for a particular accounting period has been the subject of an appeal to the First-tier Tribunal (Tax Chamber) (United Kingdom), payment of the tax charged may be postponed by agreement with the tax authorities or by application to that tribunal, such that the tax becomes payable only on determination of the appeal to that tribunal.

From the analysis of the AG

Preliminary observations

As the questions for a preliminary ruling refer to Article 49 TFEU, on freedom of establishment, and at the same time to Article 63 TFEU, on the free movement of capital, it is necessary to determine the freedom that is applicable in the dispute in the main proceedings.

In accordance with consistent case-law, in order to determine whether national legislation falls within the scope of one or other of the fundamental freedoms guaranteed by the FEU Treaty, the purpose of the legislation concerned must be taken into consideration.

In that regard, the Court has held that national legislation intended to apply only to those shareholdings which enable the holder to exert a definite influence on a company’s decisions and to determine its activities falls within the scope of Article 49 TFEU. On the other hand, national provisions which apply to shareholdings acquired solely with the intention of making a financial investment without any intention to influence the management and control of the undertaking must be examined exclusively in the light of the free movement of capital.

In this instance, the legislation at issue in the main proceedings relates to the tax treatment of disposals of assets within the same group of companies. Such legislation, as the referring court observes, may fall within the scope of Article 49 TFEU and Article 63 TFEU. Where a national measure relates to freedom of establishment and at the same time to the free movement of capital, it is necessary, in principle, in accordance with settled case-law, to examine the measure in dispute in relation to only one of those two freedoms if it appears, in the circumstances of the case in the main proceedings, that one of them is entirely secondary in relation to the other and may be considered together with it.

In this instance, I consider that freedom of establishment is the principal freedom to which the national measure at issue relates. As is clear from the order for reference, the group transfer rules apply only to disposals within a ‘group’ of companies, that concept being defined, in accordance with Section 170(3) of the TCGA 1991, as a company and all of its 75% subsidiaries (and their 75% subsidiaries). Consequently, the group transfer rules apply only (i) to transfers of assets between a parent company and the subsidiaries (or sub-subsidiaries) over which it exerts definite direct (or indirect) influence and (ii) to transfers of assets between sister subsidiaries (or sub-subsidiaries) which have a common parent company exercising common definite influence. In both cases the group transfer rules are brought into play because of the participation of the parent company, which allows it to exert definite influence over its subsidiaries. The legislation therefore relates only to relations within a group of companies and the Court has clearly established that that type of legislation chiefly affects freedom of establishment.

Furthermore, should that legislation have restrictive effects on the free movement of capital, those effects would be the unavoidable consequence of such an obstacle to freedom of establishment as there might be and do not therefore justify an independent examination of the legislation from the point of view of Article 63 TFEU. The Court should not therefore be required to determine, as GL asserts in essence, whether the situation to which the main proceedings relate falls within the scope of Article 49 TFEU on the basis not of the purpose of the legislation but of the facts of the case, nor, as a subsidiary matter, to examine the applicability of Article 63 TFEU. However, that first analysis should provide the Court with a basis on which to answer the first, second and fourth questions, which relate to the application of Article 63 TFEU.

Having regard to the foregoing, it is appropriate to answer the third, fifth and sixth questions solely in the light of Article 49 TFEU.

The third question

By its third question, the referring court asks, in essence, whether national legislation, such as the group transfer rules, which imposes an immediate tax charge on a transfer of assets from a company resident for tax purposes in the United Kingdom to a sister company which is resident for tax purposes in Switzerland (and does not carry on a trade in the United Kingdom through a permanent establishment), where both of those companies are wholly owned subsidiaries of a common parent which is resident for tax purposes in another Member State, constitutes a restriction on the freedom of establishment, within the meaning of Article 49 TFEU, of that parent company, in circumstances where such a transfer would be made on a tax-neutral basis if the sister company were also resident in the United Kingdom (or carried on a trade there through a permanent establishment).

In that regard, GL maintains that the freedom of establishment enjoyed by the Netherlands company requires that the group transfer rules also apply to a transfer of assets to existing subsidiaries of that company outside the United Kingdom, regardless of whether those subsidiaries are established in a Member State or in a third State. The United Kingdom Government contends that an immediate tax charge on the transfer of assets from a company resident in the United Kingdom to a sister company resident in Switzerland, like the 2011 disposal, does not give rise to a restriction on freedom of establishment. Lastly, the Commission claims that that type of operation does not fall within the scope of Article 49 TFEU, as Switzerland is not a Member State of the European Union.

As a preliminary point, it should be observed, first, that this question refers only to the type of transaction which corresponds to the form taken by the 2011 disposal, namely a transfer of assets from a company chargeable to tax in the United Kingdom to a company having its tax residence outside the European Union (in this instance in Switzerland) which is not chargeable to tax in the United Kingdom.

Second, the question relates to a situation in which the parent company has exercised its freedom under Article 49 TFEU by establishing a subsidiary in the United Kingdom (in this instance, GL). Freedom of establishment will therefore be examined solely from the viewpoint of the rights of the parent company (in this instance, the Netherlands company).

From that aspect, I recall that, in accordance with the Court’s consistent case-law, Article 49 TFEU, read together with Article 54 TFEU, recognises that companies formed in accordance with the legislation of a Member State and having their registered office, central administration or principal place of business in the European Union have the right to exercise their activity in other Member States through a subsidiary, branch or agency. Those provisions aim, in particular, to guarantee the benefit of national treatment in the host Member State, by prohibiting any less favourable treatment based on the place in which companies have their seat.

It follows that the (Netherlands) parent company has the right, under Article 49 TFEU, to have its subsidiary (GL) treated under the same conditions as those laid down by the United Kingdom for companies having their tax residence in the United Kingdom.

However, it must be stated that the group transfer rules at issue in the main proceedings, and in particular Section 171 of the TCGA 1992, do not entail any difference in treatment according to the place of tax residence of the parent company, since they treat a UK-resident subsidiary of a parent company having its seat in another Member State in exactly the same way as they treat a UK-resident subsidiary of a parent company having its seat in the United Kingdom. In other words, GL would have received the same tax treatment if the parent company had been resident in the United Kingdom, which, ultimately, does not entail any difference in treatment at parent-company level.

It follows that the United Kingdom does not treat the subsidiary of a company resident in another Member State less favourably than a comparable subsidiary of a company resident in the United Kingdom and that Article 49 TFEU does not preclude the imposition of an immediate tax charge in the circumstances described in the third question.

To my mind, that conclusion cannot be invalidated by the various arguments put forward by GL in support of its position that there would be a difference in treatment between the Netherlands company and a parent company resident in the United Kingdom and, consequently, a restriction on freedom of establishment.

First, GL’s argument, based on the judgment of 27 November 2008, Papillon (C‑418/07, EU:C:2008:659; ‘the judgment in Papillon’), that the appropriate comparison for the purpose of determining whether there is a difference in treatment is the comparison between the facts as they occurred (namely a transfer by a UK-resident subsidiary of a parent company not resident in the United Kingdom to a sister company not resident in the United Kingdom) and the facts of a purely domestic situation (namely a transfer by a UK-resident subsidiary of a parent company resident in the United Kingdom to a subsidiary resident in the United Kingdom), must be rejected

Contrary to GL’s contention, the case giving rise to the judgment in Papillon can be distinguished from the present case. In that case, the Court examined a regime which made the ability to elect tax integration dependant on whether the parent company held its indirect shareholdings through a subsidiary established in France or in another Member State. In that context, it was essential to take into consideration the comparability of a Community situation with a purely domestic situation and that was the approach taken by the Court. It is clear that the Court did not deliver a landmark judgment requiring a comparison, independently of the circumstances, between the actual facts and a wholly domestic situation. On the contrary, it is clear from the Court’s consistent case-law that Article 49 TFEU requires that a subsidiary of a parent company resident in another Member State be treated under the same conditions as those applied by the host country to a subsidiary of a parent company where both companies are resident in the host Member State. The comparison suggested by GL would require the host Member State to apply more favourable tax treatment to a resident subsidiary of a non-resident parent company by comparison with the treatment which it would apply to a resident subsidiary of a resident parent company.

Second, GL maintains, in essence, that whether or not there was a difference in treatment is irrelevant, in so far as, in accordance with the Court’s case-law, all measures which ‘prohibit, impede or render less attractive the exercise of the freedom of establishment’ must be regarded as restrictions on that freedom. In GL’s submission, the fact that it would not be able to transfer assets to group companies abroad without an immediate tax charge being imposed, despite the fact that the assets would remain within the same economic ownership, would render less attractive the exercise of the freedom of establishment by the Netherlands company in acquiring GL.

In that regard, it should be stated that the case-law on which GL relies, according to which there is a restriction on freedom of establishment when a measure renders ‘less attractive the exercise of [that] freedom’ covers situations which are different from that of the dispute in the main proceedings, namely situations where a company seeking to exercise its freedom of establishment in another Member State suffers a disadvantage by comparison with a similar company which does not exercise that freedom. In the absence of such a comparison, any tax charge imposed would be liable to be contrary to Article 49 TFEU, since being required to pay a tax is less attractive than being exempt from such payment. In fact, the Court’s case-law on exit tax confirms that the analysis must be carried out on the basis of the finding of a difference in treatment, and therefore of a comparison, and not merely on the basis of whether the national measures render the exercise of the freedom ‘less attractive’. By way of example, the Court has held that national measures imposing less favourable treatment on the transfer of the permanent establishment itself to another Member State by comparison with the transfer of an establishment within the Member State or the transfer of assets to an establishment located in another Member State by comparison with the transfer of assets to an establishment within the Member State, would give rise to a restriction on freedom of establishment.

However, as was indicated in points 45 and 46 of this Opinion, in the situation to which the third question refers, the national measures impose an immediate tax charge on the transfer of assets by a UK-resident subsidiary of a parent company not resident in the United Kingdom to a third country and they impose the same tax charge in the comparable situation of a transfer of assets by a UK-resident subsidiary of a UK-resident parent company to a third country.

Third, contrary to GL’s contention, the circumstances of the dispute in the main proceedings are not analogous to those of the case that gave rise to the judgment in Test Claimants II. GL relies on that judgment in support of its position that the absence of the option to defer payment, in the context of the 2011 disposal, restricts the Netherlands company’s freedom of establishment as regards the acquisition of GL, irrespective of the place of establishment of the sister company, which is not relevant for the purposes of the analysis.

However, it must be stated that the group transfer rules are materially different from the United Kingdom rules on thin capitalisation, examined in the judgment in Test Claimants II and relied on by GL. The essential characteristic of the thin capitalisation regime in the United Kingdom was that it restricted the ability of a company resident in that State to deduct the interest paid to a direct or indirect parent company resident in another Member State (or to another company controlled by that company) when it did not impose such restrictions on interest payments by a company resident in the United Kingdom to a parent company resident in the United Kingdom. The Court held that that difference in treatment applied to resident subsidiaries ‘based on the place where their parent company has its seat’ constituted a restriction on the freedom of establishment of companies established in other Member States.

Since the difference in treatment resulting from the rules on thin capitalisation was based on the place in which the parent company had its seat, that company’s freedom was restricted, both when the interest was paid directly to the parent company not resident in the United Kingdom, in another Member State, and when it was paid to another company controlled by the parent company (irrespective of the place of residence of that company). Conversely, the application of the group transfer rules to a transfer of assets by a UK-resident subsidiary of a Netherlands parent company to a sister company resident in Switzerland does not, as already emphasised above, give rise to any difference in treatment based on the place where the parent company has its seat. The group transfer rules would apply in exactly the same way if the parent company had been formed in the United Kingdom or if it were resident in the United Kingdom.

In the light of the foregoing considerations, I propose that the answer to the third question should be that Article 49 TFEU must be interpreted as not precluding national legislation relating to group transfer rules which imposes an immediate tax charge on a transfer of assets by a company resident for tax purposes in the United Kingdom to a sister company which is resident for tax purposes in Switzerland (and does not carry on a trade in the United Kingdom through a permanent establishment) in a situation where those companies are both wholly owned subsidiaries of a common parent company which has its tax residence in another Member State, and in circumstances in which such a transfer would be made on a tax-neutral basis if the sister company were resident in the United Kingdom (or carried on a trade there through a permanent establishment).

The fifth question

By its fifth question, the referring court asks, in essence, whether, if there was a restriction on freedom of establishment as a result of the group transfer rules, which would in principle be justified on overriding grounds of public interest, namely the need to preserve the balanced allocation of taxing powers, such a restriction might be considered to be necessary and proportionate, in particular in circumstances in which the taxpayer in question has realised, in consideration for the disposal of the asset, proceeds equal to the full market value of the asset.

In view of the proposed answer to the third question, there is no need to answer this question in so far as it relates to the 2011 disposal.

As regards the 2014 disposal, it is common ground between the parties to the main proceedings that the group transfer rules, and in particular Section 171 of the TCGA 1992, give rise to different tax treatment for companies chargeable to corporation tax in the United Kingdom which make intra-group transfers, depending on whether or not the transferee is chargeable to corporation tax in the United Kingdom (such as the Netherlands company). More specifically, although no tax charge arises where such a company transfers assets to a group company chargeable to tax in the United Kingdom, those rules deny such an advantage when, as here, in the context of the 2014 disposal, the transfer is made to a group company chargeable to tax in another Member State. Thus, those rules may constitute a restriction on freedom of establishment.

I am unable to subscribe to that interpretation by the parties, in so far as the group transfer rules give rise, in practice, to less favourable tax treatment of companies chargeable to corporation tax in the United Kingdom which make intra-group transfers of assets to associated companies which are not chargeable to corporation tax in the United Kingdom.

The referring court proceeds from the assumption that such a restriction may, in principle, be justified on overriding grounds of public interest, namely the need to preserve a balanced allocation of taxing powers. In other words, the United Kingdom should be authorised to tax the gains accrued before the assets are transferred to a company which is not chargeable to corporation tax in the United Kingdom. I observe, in that regard, that that assumption seems to me to be well founded. It should be pointed out that the Court has recognised that the preservation of a balanced allocation of taxing powers could in principle justify a difference in treatment between cross-border transactions and transactions carried out within the same tax jurisdiction. More specifically, as regards exit taxes, the Court has accepted that that need could justify the restriction on freedom of establishment. However, the Court has held that that justification may be accepted only if, and in so far as, it does not go beyond what is necessary to attain the objective of preserving the allocation of taxing powers between Member States.

In that context, the only question that remains, and on which the parties disagree, concerns the proportionate nature, by reference to that objective, of the immediate chargeability of the tax in question, without there being an option of deferring payment. In fact, the referring court’s question seems to relate, in reality, to the consequence flowing from the fact that GL is excluded from the benefit of the tax exemption by the group transfer rules, namely the fact that the amount of the tax due is immediately chargeable.

In that regard, GL claims that the situation at issue in the main proceedings is analogous to the situations examined by the Court concerning the exit tax, in which either a taxpayer leaves the tax jurisdiction of a Member State or assets are transferred outside that tax jurisdiction. The Court has established that it is consistent with the balanced allocation of taxing powers to calculate the amount of the tax on the date on which the assets are transferred outside the tax jurisdiction, but that the immediate imposition of a tax charge, without the option to defer payment, is disproportionate.

The United Kingdom Government observes that the objective of the national legislation is to ensure that the ordinary system for determining and collecting the tax on the actual disposal of an asset applies when the disposal has the effect of removing that asset from taxation in the United Kingdom. Having regard to that objective, the system does not go beyond what is necessary to achieve its aim by applying the ordinary taxation and collection measures (including the right to defer the tax in question by means of an appeal) to that transaction. In addition, that legislation is materially different from the legislation concerned by the Court’s case-law on exit taxes, which imposes a specific tax charge when the assets leave the tax jurisdiction of the Member State concerned, without the entity on which the tax charge is imposed disposing of those assets.

In the first place, before I examine the substance of that question, it is necessary to make certain clarifications of a procedural nature. More specifically, I recall that, in the case at issue in the main proceedings, the tribunal had held at first instance that a remedy involving an option to defer payment on an instalment basis was compatible with EU law, but that it could not give effect to such a measure (since it was not for it to decide on the precise details of an instalment payment plan) and that, instead, the tribunal left the exit tax charge disapplied. In addition, GL, having appealed against the partial closure notice relating to the 2014 disposal, deferred payment of the corporation tax pending the determination of that appeal, as it was entitled to do, under Section 55 of the TMA 1970. Consequently, GL has not been required to pay (and has not paid) the relevant corporation tax. The question that arises, therefore, is whether the fact that GL succeeded in deferring payment by lodging an appeal and applying other provisions of national law is relevant. In my view it is not. In fact, as the referring court rightly observes, if the Court considers that, in order for the national legislation to be compatible with EU law, it must have made provision for an option to defer the tax, that option must be available irrespective of whether there was any litigation.

In the second place, as regards the substance, it follows from the Court’s case-law that Member States, being entitled to tax capital gains generated when the assets in question were on their territory, have the power, for the purposes of such taxation, to make provision for a chargeable event other than the actual realisation of those gains, in order to ensure that those assets are taxed. It is apparent that a Member State may thus impose a tax charge in respect of the unrealised capital gains in order to ensure that those assets are taxed. Immediate collection in respect of unrealised capital gains has been considered by the Court to be disproportionate, however, since the unrealised capital gains do not allow the taxpayer to pay the tax and since that circumstance creates a specific disadvantage in terms of liquidity for the taxpayer when an exit tax is charged. It follows that as the immediate recovery of the exit taxes was rejected by the Court on the ground of the disadvantages in terms of liquidity for the taxpayer, it is clear that the period must be sufficiently long in order to mitigate that problem.

In the present case, the question therefore arises of the extent to which the Court’s case-law on the taxation of unrealised capital gains may be relied on in circumstances in which the capital gain is realised by the transferor of the assets. In fact, unlike exit taxes, which relate to unrealised capital gains, the group transfer rules relate to capital gains which are realised.

In that regard, as the Commission underlines, two circumstances are particularly relevant when it comes to distinguishing the capital gains realised by the transferor of the assets within a group of companies from unrealised capital gains. First is the fact that all cases of exit taxes, including cases of reinvestment, are characterised by the liquidity problem faced by a taxpayer who must pay a tax on a capital gain which he or she has not yet realised. Second is the fact that the tax authorities must ensure the tax on the capital gains realised during the period the assets were within their tax jurisdiction is paid and the risk the tax will not be paid may increase with the passage of time.

In the case of a capital gain realised by a transfer of assets, the taxpayer is not faced with a liquidity problem and may simply pay the capital gains tax with the proceeds of the assets which have been realised. In the present case, it is clear from the request for a preliminary ruling that, as regards the 2011 and 2014 disposals, it is common ground that GL received, by way of consideration, remuneration corresponding to full market value for those disposals. Consequently, the capital gains on which GL was subject to tax corresponded to the capital gains realised and GL received consideration in cash which enabled it to pay the relevant tax charges arising from those disposals. In the absence of immediate taxation, the Member State would thus be faced with the risk of non-payment, which is liable to increase with the passage of time. The assessment of proportionality in this instance is therefore different from the assessment in cases of exit taxes. Consequently, in order to ensure the proportionality of the restriction caused by the group transfer rules, it is right that no possibility of deferring payment is afforded to the taxpayer.

In the light of the foregoing considerations, I propose that the Court’s answer to the fifth question should be that Article 49 TFEU must be interpreted as meaning that a restriction on the right to freedom of establishment resulting from the difference in treatment between national and cross-border transfers of assets for consideration within a group of companies under national legislation which imposes an immediate tax charge on a transfer of assets by a company resident for tax purposes in the United Kingdom may, in principle, be justified by the need to preserve a balanced allocation of taxing powers, without there being any need to provide for the possibility of deferring payment of the charge in order to ensure the proportionate nature of that restriction, where the taxpayer concerned has realised proceeds by way of consideration for the disposal of the asset equal to the full market value of that asset.

The sixth question

By its sixth question, the referring court asks, in essence, what conclusions are to be drawn in the event of a negative answer to the fifth question, in the sense that the restriction on freedom of establishment could not be considered to be necessary and proportionate.

In the light of the proposed answer to the fifth question, there is no need to answer the sixth question.

Copyright – internationaltaxplaza.info