On December 14, 2023 on the website of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) the judgment of the CJEU in Case C‑457/21 P, the European Commission versus the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, Amazon.com Inc and Amazon EU Sàrl with Ireland as intervener at first instance, ECLI:EU:C:2023:985, was published.

Background to the dispute

2 The background to the dispute was set out in paragraphs 1 to 71 of the judgment under appeal, in its public version, as follows:

‘1 Amazon.com, Inc., which has its registered office in the United States, and the companies under its control (together, “the Amazon group”) carry on online activities, including online retail transactions and the provision of various online services. To that end, the Amazon group manages several internet sites in various languages of the European Union, including amazon.de, amazon.fr, amazon.it and amazon.es.

2 Prior to May 2006, the Amazon group’s European business was managed from the United States. In particular, retail and service activities on the EU websites were carried out by two entities established in the United States, namely Amazon.com International Sales, Inc. (“AIS”) and Amazon International Marketplace (“AIM”), as well as by [other entities] established in France, Germany and the United Kingdom.

3 In 2003, a restructuring of the Amazon group’s business in Europe was planned. That restructuring, which was in fact carried out in 2006 (“the 2006 restructuring”), was structured around the formation of two companies established in Luxembourg (Luxembourg). More specifically, the companies in question were, first, Amazon Europe Holding Technologies SCS (“LuxSCS”), a Luxembourg limited partnership, the partners of which were United States companies, and, secondly, Amazon EU Sàrl (“LuxOpCo”), which, like LuxSCS, had its registered office in Luxembourg.

4 LuxSCS first concluded several agreements with certain Amazon group entities established in the United States, namely:

– licence and assignment agreements for pre-existing intellectual property (together, “the Buy-In Agreement”) with Amazon Technologies, Inc. (“ATI”), an Amazon group entity established in the United States;

– a cost-sharing agreement (“the CSA”) concluded in 2005 with ATI and A9.com, Inc. (“A9”), an Amazon group entity established in the United States. Under the Buy-In Agreement and the CSA, LuxSCS obtained the right to exploit certain intellectual property rights and “derivative works” thereof, which were owned and further developed by A9 and ATI. The intangible assets covered by the CSA consisted essentially of three categories of intellectual property, namely technology, customer data and trade marks. Under the CSA and the Buy-In Agreement, LuxSCS could also sub-license the intangible assets, in particular with a view to operating the EU websites. In return for those rights, LuxSCS was required to pay Buy-In payments and its annual share of the costs related to the CSA development programme.

5 Secondly, LuxSCS entered into a licence agreement with LuxOpCo, which took effect on 30 April 2006, relating to the abovementioned intangible assets (“the Licence Agreement”). Under that agreement, LuxOpCo obtained the right to use the intangible assets in exchange for the payment of a royalty to LuxSCS (“the royalty”).

6 Lastly, LuxSCS concluded an agreement for the licensing and assignment of intellectual property rights with Amazon.co.uk Ltd, Amazon.fr SARL and Amazon.de GmbH, under which LuxSCS received certain trade marks and the intellectual property rights in respect of the EU websites.

7 In 2014, the Amazon group underwent a second restructuring and the contractual arrangement between LuxSCS and LuxOpCo was no longer applicable.

A. The tax ruling at issue

8 In preparation for the 2006 restructuring, Amazon.com and a tax adviser, by letters of 23 and 31 October 2003, requested the Luxembourg tax administration to issue a tax ruling confirming the treatment of LuxOpCo and LuxSCS for the purposes of Luxembourg corporate income tax.

9 By its letter of 23 October 2003, Amazon.com requested approval for the method of calculating the rate of the royalty that LuxOpCo was to pay to LuxSCS from 30 April 2006. That request by Amazon.com was based on a transfer pricing report prepared by its tax advisers (“the 2003 transfer pricing report”). The authors of that report proposed, in essence, a transfer pricing arrangement which, in their view, enabled the determination of the corporate income tax liability which LuxOpCo was required to pay in Luxembourg. More specifically, by [that] letter …, Amazon.com had requested confirmation that the transfer pricing arrangement determining the rate of the annual royalty that LuxOpCo was to pay to LuxSCS under the Licence Agreement, as set out in the 2003 transfer pricing report, would result in an “appropriate and acceptable profit” for LuxOpCo with respect to the transfer pricing policy and Article 56 and Article 164(3) of the loi du 4 décembre 1967 concernant l’impot sur le revenue, telle que modifiée (Law of 4 December 1967 on income tax, as amended) …

10 By letter of 31 October 2003, drafted by another tax adviser, Amazon.com requested confirmation of the tax treatment of LuxSCS, of its partners established in the United States and of the dividends received by LuxOpCo as part of that structure. The letter explained that LuxSCS, as a “Société en Commandite Simple”, did not have a separate tax personality from that of its partners and that, as a result, it was not subject to corporate income tax or net wealth tax in Luxembourg.

11 On 6 November 2003, the Administration des contributions directes du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg (“the Luxembourg tax administration” or “the Luxembourg tax authorities”) sent Amazon.com a letter (“the tax ruling at issue”) which reads, in part, as follows:

“Sir,

After having made myself acquainted with the letter of [O]ctober 31, 2003, directed to me by [your tax advisor] just as with your letter of [O]ctob[er] 23, 2003 and dealing with your position regarding Luxembourg tax treatment within the framework of your future activities, I am pleased to inform you that I may approve the contents of the two letters. …’

12 At the request of Amazon.com, the Luxembourg tax administration extended the validity of the tax ruling at issue in 2010 and effectively applied it until June 2014, when the European structure of the Amazon group was modified. Thus, the tax ruling at issue was applied from 2006 to 2014 (“the relevant period”).

B. The administrative procedure before the Commission

13 On 24 June 2014, the European Commission requested that the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg provide information on the tax rulings granted to the Amazon group. On 7 October 2014, it published the decision to initiate a formal investigation procedure under Article 108(2) TFEU.

…

15 [In the context of that procedure,] Amazon.com submitted to the Commission a new transfer pricing report drawn up by a tax adviser, the purpose of which was to verify ex post whether the royalty paid by LuxOpCo to LuxSCS in accordance with the tax ruling at issue complied with the arm’s length principle (“the 2017 transfer pricing report”).

C. [The decision at issue]

16 On 4 October 2017, the Commission adopted [the decision at issue].

17 Article 1 of that decision reads, in part, as follows:

“The [tax ruling at issue], by virtue of which Luxembourg endorsed a transfer pricing arrangement […] that allowed [LuxOpCo] to assess its corporate income tax liability in Luxembourg from 2006 to 2014 and the subsequent acceptance of the yearly corporate income tax declaration based thereon constitutes [State] aid […]’

1 Presentation of the factual and legal context

…

(a) Presentation of the Amazon group

…

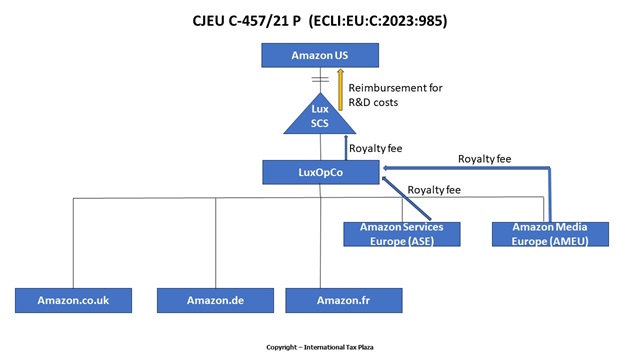

21 The European structure of the Amazon group during the relevant period was presented by the Commission in the following schematic form:

22 First, with regard to LuxSCS, the Commission pointed out that that company did not have any physical presence or employees in Luxembourg. According to the Commission, during the relevant period, LuxSCS functioned solely as an intangible assets holding company for the Amazon group’s European operations, for which LuxOpCo was responsible as the principal operator. It stated, however, that LuxSCS had also granted intra-group loans to several entities in the Amazon group. The Commission also noted that LuxSCS was a party to several intra-group agreements with ATI, A9 and LuxOpCo …

23 Secondly, as regards LuxOpCo, the Commission placed particular emphasis on the fact that, during the relevant period, LuxOpCo was a wholly owned subsidiary of LuxSCS.

24 According to the Commission, as from the 2006 restructuring of the Amazon group’s European operations, LuxOpCo functioned as the Amazon group’s headquarters in Europe and the principal operator of the Amazon group’s European online retail and service business as carried out through the EU websites. The Commission stated that, in that capacity, LuxOpCo had to manage decision-making related to the retail and service businesses carried out through the EU websites, along with managing key physical components of the retail business. In addition, as the seller of record of the Amazon group’s inventory in Europe, LuxOpCo was also responsible for managing inventory on the EU websites. It held title to that inventory and bore the risks and losses. The Commission further stated that LuxOpCo had recorded revenue in its accounts both from product sales and from order fulfilment. Lastly, LuxOpCo also performed treasury management functions for the Amazon group’s European operations.

25 Next, the Commission indicated that LuxOpCo had held shares in Amazon Services Europe (“ASE”) and Amazon Media Europe (“AMEU”), two Amazon group entities resident in Luxembourg, and also in the subsidiaries of Amazon.com established in the United Kingdom, France and Germany (“the EU local affiliates”), which performed various intra-group services in support of LuxOpCo’s business. During the relevant period, ASE operated the Amazon group’s EU third-party seller business, “Marketplace”. AMEU operated the Amazon group’s EU digital business, such as, for example, the sale of MP3s and eBooks. The EU local affiliates supplied services relating to the operation of the EU websites.

26 The Commission added that, during the relevant period, ASE and AMEU, both Luxembourg resident companies, formed a fiscal unity with LuxOpCo for Luxembourg tax purposes in which LuxOpCo operated as the parent of the unity. Those three entities therefore constituted a single taxpayer.

27 Lastly, in addition to the Licence Agreement concluded between LuxOpCo and LuxSCS, the Commission described in detail certain other intra-group agreements to which LuxOpCo was a party during the relevant period, namely certain service agreements concluded on 1 May 2006 with the EU local affiliates and intellectual property licence agreements concluded on 30 April 2006 with ASE and AMEU, under which ASE and AMEU were granted non-exclusive sub-licences to the intangible assets.

(b) Presentation of the tax ruling at issue

28 Having examined the structure of the Amazon group, the Commission describes the tax ruling at issue.

29 In that regard, first, it referred to the letters of 23 and 31 October 2003, mentioned in paragraphs 8 to 10 [of the judgment under appeal].

30 Secondly, the Commission explained the content of the 2003 transfer pricing report on the basis of which the method for establishing the royalty was proposed.

31 The Commission began by indicating that the 2003 transfer pricing report provided a functional analysis of LuxSCS and LuxOpCo, according to which LuxSCS’s principal activities were limited to those of an intangible assets holding company and a participant in the ongoing development of the intangible assets through the CSA. LuxOpCo was described in that report as managing strategic decision-making related to the EU websites’ retail and service businesses, and also managing the key physical components of the retail business.

32 Next, the Commission stated that the 2003 transfer pricing report contained a section dealing with the selection of the most appropriate transfer pricing method for determining whether the royalty rate complied with the arm’s length principle. Two methods were considered in the report: one based on the comparable uncontrolled price method (“the CUP method”) and another based on the residual profit split method.

33 Applying the CUP method, the 2003 transfer pricing report calculated an arm’s length range for the royalty rate of 10.6 to 13.6% on the basis of a comparison with an agreement between Amazon.com and a retailer in the United States …

34 Applying the residual profit split method, the 2003 transfer pricing report estimated the return associated with LuxOpCo’s “routine functions in its role as the European operating company” based on a mark-up on costs to be incurred by LuxOpCo. To that end, the “net cost plus mark-up” was considered the profit level indicator for the purpose of determining the arm’s length remuneration for the anticipated functions of LuxOpCo. It was proposed that a mark-up of [confidential] be applied to LuxOpCo’s adjusted operating costs. The Commission observed that, according to the 2003 transfer pricing report, the difference between that return and LuxOpCo’s operating profit constituted the residual profit, which was wholly attributable to the use of the intangible assets licensed from LuxSCS. The Commission also stated that, on the basis of that calculation, the authors of the 2003 transfer pricing report had concluded that a royalty rate in a range of 10.1% to 12.3% of LuxOpCo’s net revenues would be consistent with the arm’s length standard under the guidelines of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

35 Lastly, the Commission stated that the authors of the 2003 transfer pricing report had considered that the results converged and had indicated that the arm’s length range for the royalty rate from LuxOpCo to LuxSCS was 10.1% to 12.3% of LuxOpCo’s sales. However, the authors of the 2003 transfer pricing report considered that the residual profit split analysis was more reliable and should therefore be selected.

36 Thirdly, … the Commission stated that, by the tax ruling at issue, the Luxembourg tax administration had accepted that the arrangement for determining the level of the royalty, which in turn had determined LuxOpCo’s annual taxable income in Luxembourg, was at arm’s length. It added that [that decision] was relied upon by LuxOpCo when filing its annual tax declarations.

(c) Description of the relevant national legal framework

37 As regards the relevant national legal framework, the Commission cited Article 164(3) of the [Law on income tax]. According to that provision, “taxable income comprises hidden profit distributions” and “a hidden profit distribution arises in particular when a shareholder, a stockholder or an interested party receives either directly or indirectly benefits from a company or an association which he normally would not have received if he had not been a shareholder, a stockholder or an interested party”. In that context, the Commission explained, in particular, that, during the relevant period, Article 164(3) of the [Law on income tax] was interpreted by the Luxembourg tax administration as enshrining the arm’s length principle in Luxembourg tax law.

(d) Presentation of the OECD transfer pricing framework

38 In recitals 244 to 249 of the [decision at issue], the Commission presented the OECD transfer pricing framework. According to the Commission, “transfer prices”, as understood by the OECD in the guidelines published by that organisation in 1995, 2010 and 2017, are the prices at which a company transfers physical goods or intangible property or provides services to its associated companies. According to the arm’s length principle, as applied in corporate taxation, national tax administrations should only accept the transfer prices agreed between associated group companies for intra-group transactions if those prices reflect what would have been agreed in uncontrolled transactions, that is to say, transactions between independent companies negotiating under comparable circumstances on the market. In addition, the Commission stated that the arm’s length principle is based on the separate entity approach, according to which the members of a corporate group are treated as separate entities for tax purposes.

39 The Commission also indicated that the 1995, 2010 and 2017 OECD Guidelines list five methods for establishing arm’s length pricing for intra-group transactions. Only three of them were relevant for the [decision at issue], namely the CUP method, the transactional net margin method (“the TNMM”) and the transactional profit split method. The Commission described those methods in recitals 250 to 256 of the [decision at issue].

2 Assessment of the tax ruling at issue

…

44 As regards the third condition for the existence of State aid [laid down in Article 107(1) TFEU], the Commission explained that, where a tax ruling endorses a result that does not reflect in a reliable manner what would result from a normal application of the ordinary tax system, without justification, that ruling will confer a selective advantage on its addressee in so far as that selective treatment results in a lowering of that taxpayer’s tax liability as compared to companies in a similar factual and legal situation. The Commission also considered that, in the present case, the tax ruling at issue had conferred a selective advantage on LuxOpCo by lowering its corporate income tax liability in Luxembourg.

(a) Analysis of the existence of an advantage

…

46 As a preliminary point, the Commission stated that, in respect of tax measures, an advantage for the purposes of Article 107 TFEU may be granted by reducing an undertaking’s taxable base or the amount of tax due from it. In recital 402 of the [decision at issue], it noted that, according to the Court of Justice, in order to decide whether a method of assessment of taxable income confers an advantage on its beneficiary, it is necessary to compare that method with the ordinary tax system, based on the difference between profits and outgoings of an undertaking carrying on its activities in conditions of free competition. Consequently, according to the Commission, “a tax ruling that enables a taxpayer to employ transfer prices in its intra-group transactions that do not resemble prices which would be charged in conditions of free competition between independent undertakings negotiating under comparable circumstances at arm’s length confers an advantage on that taxpayer, in so far as it results in a reduction of the company’s taxable income and thus its taxable base under the ordinary corporate income tax system”.

47 In the light of those considerations, the Commission concluded, in recital 406 of the [decision at issue], that, in order to establish that the tax ruling at issue confers an economic advantage on LuxOpCo, it had to demonstrate that the transfer pricing arrangement endorsed in the tax ruling at issue produced an outcome that departed from a reliable approximation of a market-based outcome, resulting in a reduction of LuxOpCo’s taxable basis for corporate income tax purposes. According to the Commission, the tax ruling at issue had produced such an outcome.

48 That conclusion is based on a primary finding and three subsidiary findings.

(1) The primary finding of an advantage

49 In … [the decision at issue], … the Commission considered that, by endorsing a transfer pricing arrangement that attributed a remuneration to LuxOpCo solely for “routine” functions and that attributed the entire profit generated by LuxOpCo in excess of that remuneration to LuxSCS in the form of a royalty payment, the tax ruling at issue had produced an outcome that departed from a reliable approximation of a market-based outcome.

50 In essence, by its primary line of reasoning, the Commission considered that the functional analysis of LuxOpCo and LuxSCS set out by the authors of the 2003 transfer pricing report and ultimately accepted by the Luxembourg tax administration was incorrect and could not result in an arm’s length outcome. On the contrary, the Luxembourg tax administration should have concluded that LuxSCS did not perform any “unique and valuable” functions in relation to the intangible assets for which it merely held the legal title.

…

62 In concluding its primary finding of an economic advantage for the purpose of Article 107(1) TFEU, the Commission indicated that an “arm’s length remuneration” for LuxSCS under the Licence Agreement should have been equal to the sum of the Buy-In and CSA costs incurred by LuxSCS, without a mark-up, plus any relevant costs incurred directly by LuxSCS, to which a mark-up of 5% had to be applied, to the extent that those costs reflected actual functions performed by LuxSCS. In the Commission’s view, that remuneration reflected what an independent party in a position similar to that of LuxOpCo would have been willing to pay for the rights and obligations assumed under the Licence Agreement. In addition, according to the Commission, that level of remuneration would have been sufficient to enable LuxSCS to cover its payment obligations under the Buy-In Agreement and the CSA (recitals 559 and 560 of the [decision at issue]).

63 According to the Commission, since the level of LuxSCS’s remuneration calculated by the Commission was lower than the level of LuxSCS’s remuneration resulting from the transfer pricing arrangement endorsed by the tax ruling at issue, that ruling conferred an advantage on LuxOpCo in the form of a reduction of its taxable base for the purposes of Luxembourg corporate income tax as compared to the income of companies whose taxable profit reflected prices negotiated at arm’s length on the market (recital 561 of the [decision at issue]).

(2) The subsidiary findings of an advantage

64 In … [the decision at issue], … the Commission sets out its subsidiary finding of an advantage, according to which, even if the Luxembourg tax administration were right to have accepted the analysis of LuxSCS’s functions set out in the 2003 transfer pricing report, the transfer pricing arrangement endorsed by the tax ruling at issue was, in any event, based on inappropriate methodological choices that produced an outcome which departed from a reliable approximation of a market-based outcome. The Commission specified that the purpose of its assessment … was not to determine a precise arm’s length remuneration for LuxOpCo but rather to demonstrate that the tax ruling at issue had conferred an economic advantage, since the endorsed transfer pricing arrangement was based on three inappropriate methodological choices which resulted in a lowering of LuxOpCo’s taxable income as compared to companies whose taxable profit reflected prices negotiated at arm’s length on the market.

65 In that context, the Commission made three separate subsidiary findings.

66 In its first subsidiary finding, the Commission stated that LuxOpCo had been inaccurately considered to perform only “routine” management functions and that the profit split method, together with the contribution analysis, ought to have been applied.

…

(b) Selectivity of the measure

69 In Section 9.3 of the [decision at issue], entitled “Selectivity”, the Commission set out the reasons why it considered that the measure at issue was selective.

(c) Identification of the beneficiary of the aid

70 In … [the decision at issue], … the Commission considered that any favourable tax treatment granted to LuxOpCo had also benefited the Amazon group as a whole by providing it with additional resources, with the result that the group had to be regarded as a single unit benefiting from the contested aid measure.

71 … [The] Commission stated [there also] that, since the aid measure was granted every year in which LuxOpCo’s annual tax declaration was accepted by the Luxembourg tax administration, the Amazon group could not object to the recovery of that aid on the basis of the limitation period. In recitals 639 to 645 of the [decision at issue], the Commission set out the methodology for recovery.’

The procedure before the General Court and the judgment under appeal

3 By application lodged with the Registry of the General Court on 14 December 2017, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg brought the action in Case T‑816/17, seeking, principally, the annulment of the decision at issue and, in the alternative, the annulment of that decision in so far as it ordered the recovery of the aid identified in that decision.

4 By application lodged at the Registry of the General Court on 22 May 2018, Amazon EU Sàrl and Amazon.com (together, ‘Amazon’) brought the action in Case T‑318/18, seeking, principally, the annulment of Articles 1 to 4 of the decision at issue and, in the alternative, the annulment of Articles 2 to 4 of that decision.

5 In support of their actions, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and Amazon had raised five and nine pleas in law respectively, which the General Court considered to be largely overlapping as follows:

– in the first place, in the first plea in Case T‑816/17 and in the first to fourth pleas in Case T‑318/18, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and Amazon disputed, in essence, the Commission’s primary finding that there was an advantage in favour of LuxOpCo for the purpose of Article 107(1) TFEU;

– in the second place, in the third complaint in the second part of the first plea in Case T‑816/17 and in the fifth plea in Case T‑318/18, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and Amazon disputed the Commission’s subsidiary findings concerning the existence of a tax advantage in favour of LuxOpCo within the meaning of that provision;

– in the third place, in the second plea in Case T‑816/17 and in the sixth and seventh pleas in Case T‑318/18, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and Amazon disputed the Commission’s primary and subsidiary findings in respect of the selectivity of the tax ruling at issue;

– in the fourth place, in the third plea in Case T‑816/17, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg submitted that the Commission had infringed the Member States’ exclusive competence in the area of direct taxation;

– in the fifth place, in the fourth plea in Case T‑816/17 and in the eighth plea in Case T‑318/18, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and Amazon maintained that the Commission had infringed their rights of defence;

– in the sixth place, in the second part of the first plea and the first complaint in the second part of the second plea in Case T‑816/17 and in the eighth plea in Case T‑318/18, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and Amazon disputed the relevance in the present case of the 2017 version of the OECD Guidelines, as used by the Commission in adopting the decision at issue; and

– in the seventh place, in the fifth plea, relied on in support of the form of order sought in the alternative in Case T‑816/17 and in the ninth plea in Case T‑318/18, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and Amazon called into question the merits of the Commission’s reasoning concerning the recovery of the aid ordered by that institution.

6 In its intervention at first instance, Ireland alleged, first, infringement of Article 107 TFEU in that the Commission had not established the existence of an advantage in favour of LuxOpCo; secondly, infringement of Article 107 TFEU in that the Commission had failed to prove the selectivity of the measure; thirdly, infringement of Articles 4 and 5 TEU in that the Commission had engaged in disguised tax harmonisation; and, fourthly, infringement of the principle of legal certainty in so far as the decision at issue had ordered the recovery of the aid identified in that decision.

7 Having joined Cases T‑816/17 and T‑318/18 for the purposes of the judgment under appeal, by that judgment the General Court annulled the decision at issue.

8 First, it upheld the first and second complaints in the second part and the third part of the first plea in Case T‑816/17 and the second and fourth pleas in Case T‑318/18, claiming that the Commission had not demonstrated the existence of an advantage in the context of its primary finding.

9 In that regard, it held, first, that the Commission had erred in finding that LuxSCS had to be used as the tested party for the purposes of the application of the TNMM and, second, that the calculation of ‘LuxSCS’s remuneration’ carried out by the Commission, on the basis of the premiss that LuxSCS had to be the tested entity, was vitiated by numerous errors and could not be regarded as being sufficiently reliable or capable of achieving an arm’s length outcome. Since the calculation method used by the Commission had to be rejected, the General Court found that that method could not serve as a basis for the finding that the royalty paid to LuxSCS should have been lower than the royalty it actually received, pursuant to the tax ruling at issue, during the relevant period. Thus, as regards the primary finding of an advantage, the elements relied on by the Commission did not make it possible, according to the General Court, to establish that LuxOpCo’s tax burden had been artificially reduced as a result of an overpricing of the royalty (paragraphs 296 and 297 of the judgment under appeal).

10 Next, the General Court upheld the pleas and arguments of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and Amazon challenging the merits of the Commission’s three subsidiary findings regarding the existence of an advantage. In that respect it found:

– as regards the first subsidiary finding, that the Commission, in wrongly concluding that LuxOpCo’s functions in connection with commercial activities were ‘unique and valuable’ and in failing to seek to identify whether there were external data available from independent undertakings in order to determine the value of the contributions made by LuxSCS and LuxOpCo respectively, had not duly justified that the profit split method, together with the contribution analysis, which it used was the appropriate method for determining transfer pricing in the present case (paragraphs 503 to 507 of the judgment under appeal). The General Court, furthermore, found that the Commission, in particular in that it had not sought to ascertain the correct allocation key for the combined profits of LuxSCS and LuxOpCo that would have been appropriate had those parties been independent undertakings, or even to identify specific factors from which it could be determined that LuxOpCo’s functions in connection with the development of the intangible assets or with its role as headquarters would have conferred entitlement to a greater share of profits as compared with the share of profits actually obtained pursuant to the tax ruling at issue, had not succeeded in establishing that, if the profit split method it used had been applied, LuxOpCo’s remuneration would have been greater and, therefore, that that decision had conferred on that company an economic advantage (paragraphs 518 and 530 of the judgment under appeal).

– as regards the second subsidiary finding, that the Commission was required to show that the error it had identified in the choice of profit level indicator for LuxOpCo used in the tax ruling had led to a reduction in the tax burden of the recipient of that decision, which meant answering the question of which profit level indicator was appropriate. Having regard to the interpretation given by the Commission to the decision at issue, the General Court held that the Commission had not sought to ascertain the arm’s length remuneration of LuxOpCo or, a fortiori, whether LuxOpCo’s remuneration, endorsed by the tax ruling at issue, was lower than the remuneration that it would have received under arm’s length conditions (paragraphs 546 and 547 of the judgment under appeal);

– as regards the third subsidiary finding, that, while the Commission had been correct to find that the ceiling mechanism in the remuneration of LuxOpCo based on a percentage of its annual sales was a methodological error, it had not however shown that that mechanism had had an impact on the arm’s length nature of the royalty paid by LuxOpCo to LuxSCS. Consequently, it held that the sole finding that the ceiling had been applied for 2006, 2007 and 2011 to 2013 was not sufficient to establish that LuxOpCo’s remuneration received in respect of those years did not correspond to an approximation of an arm’s length outcome and, therefore, that, by its third subsidiary finding, the Commission had not demonstrated the existence of an advantage for LuxOpCo (paragraphs 575, 576, 585, 586 and 588 of the judgment under appeal).

11 In the light of those findings, which it considered to be sufficient to lead to the annulment of the decision at issue, the General Court did not examine the other pleas and arguments of the parties.

The procedure before the Court of Justice and the forms of order sought by the parties to the appeal

12 By its appeal, the Commission claims that the Court should:

– set aside the judgment under appeal;

– reject the first plea in Case T‑816/17 and the second, fourth, fifth and eighth pleas in Case T‑318/18;

– refer the case back to the General Court for consideration of the pleas not already assessed;

– alternatively, make use of its power under the second sentence of the first paragraph of Article 61 of the Statute of the Court of the Justice of the European Union to give final judgment in the matter; and

– reserve the costs, if it refers the case back to the General Court, or order the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and Amazon to pay the costs of the proceedings, if the Court of Justice gives final judgment in the matter.

13 The Grand Duchy of Luxembourg contends that the Court should:

– dismiss the appeal;

– in the alternative, refer the case back to the General Court; and

– order the Commission to bear the costs.

14 Amazon contends that the Court should:

– dismiss the appeal; and

– order the Commission to bear the costs.

The appeal

Admissibility

15 The Grand Duchy of Luxembourg submits, without formally presenting a plea of inadmissibility, that the arguments advanced in support of the first part of the first ground of appeal and the second part of the second ground of appeal relating to the interpretation and application of the arm’s length principle are inadmissible in that they seek to call into question the findings of fact of the General Court. To the extent that the Commission does not seek to demonstrate the distortion of those facts, for it to dispute them in the context of an appeal is inadmissible. In addition, hypothetical errors by the General Court in the interpretation and application of the arm’s length principle must be regarded as relating to Luxembourg national law, since, according to the case-law of the Court of Justice, that principle is not an autonomous principle of EU law, and so they must be regarded as errors of fact. Questions of fact cannot be raised in the context of an appeal, subject to cases of distortion of the facts by the General Court. The arguments are therefore also, for that reason, inadmissible, since the distortions alleged by the Commission are unsubstantiated.

16 Amazon, for its part, submits, without formally raising a plea of inadmissibility, that the Commission seeks to present the General Court’s assessment of fact as questions of law or legal interpretation so that the Court of Justice re-examines the facts. However, the Court, in accordance with Article 256 TFEU and Article 58 of the Statute of the Court of Justice of the European Union, may rule on questions of law only, unless there is a distortion, which the Commission merely asserts without even attempting to substantiate that assertion. To that extent, the appeal and, in particular, the first part of the first ground and the second part of the second ground are inadmissible.

17 It should be pointed out that the Commission submits, inter alia, in paragraph 25 of its appeal, that ‘a misinterpretation and misapplication of the [arm’s length principle] constitutes an infringement of Article 107(1) TFEU in relation to the condition of advantage’ and, in paragraph 26 thereof, that ‘where the General Court misinterprets and misapplies the [arm’s length principle], it commits an error “in carrying out its assessment under Article 107(1) TFEU”’. It repeats that complaint in Section 6.2 of the appeal.

18 Consequently, irrespective of the reasons why the Commission considers that the General Court, in particular in paragraphs 162 to 251 of the judgment under appeal, misinterpreted and misapplied the arm’s length principle, it must be held that that institution invites the Court of Justice to review the correct interpretation and proper application of that principle by the General Court in the light of Article 107(1) TFEU.

19 In that regard, it should be recalled that the jurisdiction of the Court of Justice ruling on an appeal against a decision given by the General Court is defined by the second subparagraph of Article 256(1) TFEU. That provision states that an appeal is to be on points of law only and that it must be made ‘under the conditions and within the limits laid down by the Statute’. In a list setting out the grounds that may be relied upon in that context, the first paragraph of Article 58 of the Statute of the Court of Justice of the European Union states that an appeal may be based on infringement of EU law by the General Court (judgment of 5 July 2011, Edwin v OHIM, C‑263/09 P, EU:C:2011:452, paragraph 46).

20 It is true that, in principle, with respect to the assessment in the context of an appeal of the General Court’s findings on national law, which, in the field of State aid, constitute findings of fact, the Court of Justice has jurisdiction only to determine whether there was a distortion of that law (see, to that effect, judgment of 8 November 2022, Fiat Chrysler Finance Europe v Commission, C‑885/19 P and C‑898/19 P, EU:C:2022:859, paragraph 82 and the case-law cited). The Court cannot however be deprived of the possibility of reviewing whether those assessments are not themselves a breach of EU law within the meaning of the case-law cited in paragraph 19 of the present judgment.

21 The question whether the General Court adequately defined the relevant reference system and, by extension, correctly interpreted and applied the provisions comprising it, in this case the arm’s length principle, is a question of law which can be reviewed by the Court of Justice on appeal. The arguments aimed at calling into question the choice of reference system or its significance as part of the first step of the analysis of the existence of a selective advantage are admissible, since that analysis derives from a legal classification of national law on the basis of a provision of EU law (see, to that effect, judgments of 8 November 2022, Fiat Chrysler Finance Europe v Commission, C‑885/19 P and C‑898/19 P, EU:C:2022:859, paragraph 85, and of 5 December 2023, Luxembourg and Others v Commission, C‑451/21 P and C‑454/21 P, EU:C:2023:948, paragraph 78).

22 To hold that the Court is not permitted to determine whether it was without erring in law that the General Court ruled on the definition, interpretation and application by the Commission of the relevant reference system, which is a decisive parameter for the purposes of examining whether there was a selective advantage, would amount to accepting the possibility that the General Court could have, as the case may be, infringed a provision of primary EU law, namely Article 107(1) TFEU, without it being possible to penalise that infringement in the context of an appeal, which could contravene the second subparagraph of Article 256(1) TFEU, as has been pointed out in paragraph 19 of the present judgment.

23 It must therefore be held that, by inviting the Court to review whether the General Court had correctly interpreted and applied the arm’s length principle in the light of Article 107(1) TFEU, in order to rule on whether the reference system used by the Commission for the purpose of defining normal taxation was incorrect and, therefore, that the existence of an advantage for the benefit of the Amazon group was not established, the Commission has presented grounds and arguments which, contrary to the submissions of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and Amazon, are admissible.

Substance

24 In support of its appeal, the Commission advances two grounds, alleging, first, errors committed by the General Court regarding the primary finding of an advantage set out by it in the decision at issue and, second, errors by the General Court relating to the first subsidiary finding that it made as regards that advantage.

25 It is appropriate to examine these two grounds of appeal together.

Arguments of the parties

26 The Commission’s first ground of appeal contains two parts. The first part alleges that the General Court, in paragraphs 162 to 251 of the judgment under appeal, misinterpreted and misapplied the arm’s length principle, failed adequately to state reasons on that point and infringed the rules of procedure by rejecting the functional analysis of LuxSCS and the choice of that company as the tested party in the decision at issue. The second part alleges an error resulting from the rejection, by the General Court, in paragraphs 257 to 295 of that judgment, of the calculation of the arm’s length level of the royalty.

27 In support of this ground, the Commission submits, first of all, that, as the General Court itself found, normal taxation should, in the present case, be assessed having regard to the arm’s length principle, which constitutes a ‘tool’ which it must use in order to determine whether there is an advantage within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU. Therefore, by interpreting and applying that principle incorrectly, the General Court breached that provision. In any event, the Commission submits that, although the General Court’s errors in the application of that principle only concern Luxembourg law, those errors nonetheless constitute clear distortions of that law, which the General Court found to be well founded on that same principle.

28 The Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and Amazon dispute all of the arguments relied on in support of the first ground of appeal.

29 The Grand Duchy of Luxembourg notably observes in its response that, at the time of the adoption of the tax ruling at issue, as well as when that decision was extended, Luxembourg law made no reference to the OECD Guidelines. Those guidelines are not binding on member States of that organisation, but may clarify the relevant provisions of Luxembourg law.

30 The second ground of appeal, which refers to paragraphs 314 to 442 and 499 to 538 of the judgment under appeal, challenges the rejection by the General Court of the first subsidiary finding made by the Commission in the decision at issue. In the second part of the second ground of appeal, the Commission once again submits, in Section 6.2 of the appeal, that ‘the General Court misinterpreted and misapplied the [arm’s length principle]’, which both the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and Amazon dispute.

Findings of the Court

31 According to the settled case-law of the Court, action by Member States in areas that are not subject to harmonisation by EU law is not excluded from the scope of the provisions of the FEU Treaty on monitoring State aid. The Member States must thus refrain from adopting any tax measure liable to constitute State aid that is incompatible with the internal market (judgment of 8 November 2022, Fiat Chrysler Finance Europe v Commission, C‑885/19 P and C‑898/19 P, EU:C:2022:859, paragraph 65 and the case-law cited).

32 In that regard, it follows from the well-established case-law of the Court that the classification of a national measure as ‘State aid’, within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU, requires all the following conditions to be fulfilled. First, there must be an intervention by the State or through State resources. Second, the intervention must be liable to affect trade between Member States. Third, it must confer a selective advantage on the beneficiary. Fourth, it must distort or threaten to distort competition (judgment of 8 November 2022, Fiat Chrysler Finance Europe v Commission, C‑885/19 P and C‑898/19 P, EU:C:2022:859, paragraph 66 and the case-law cited).

33 So far as concerns the condition relating to selective advantage, it requires a determination as to whether, under a particular legal regime, the national measure at issue is such as to favour ‘certain undertakings or the production of certain goods’ over other undertakings which, in the light of the objective pursued by that regime, are in a comparable factual and legal situation and which accordingly suffer different treatment that can, in essence, be classified as discriminatory (judgment of 8 November 2022, Fiat Chrysler Finance Europe v Commission, C‑885/19 P and C‑898/19 P, EU:C:2022:859, paragraph 67 and the case-law cited).

34 In order to classify a national tax measure as ‘selective’, the Commission must begin by identifying the reference system, that is the ‘normal’ tax system applicable in the Member State concerned, and demonstrate, as a second step, that the tax measure at issue is a derogation from that reference system, in so far as it differentiates between operators who, in the light of the objective pursued by that system, are in a comparable factual and legal situation. The concept of ‘State aid’ does not, however, cover measures that differentiate between undertakings which, in the light of the objective pursued by the legal regime concerned, are in a comparable factual and legal situation, and are, therefore, a priori selective, where the Member State concerned is able to demonstrate, as a third step, that that differentiation is justified, in the sense that it flows from the nature or general structure of the system of which those measures form part (see judgment of 8 November 2022, Fiat Chrysler Finance Europe v Commission, C‑885/19 P and C‑898/19 P, EU:C:2022:859, paragraph 68 and the case-law cited).

35 The determination of the reference system is of particular importance in the case of tax measures, as has been emphasised in paragraph 23 of the present judgment, since the existence of an economic advantage for the purposes of Article 107(1) TFEU may be established only when compared with ‘normal’ taxation.

36 Thus, determination of the set of undertakings which are in a comparable factual and legal situation depends on the prior definition of the legal regime in the light of whose objective it is necessary, where applicable, to examine whether the factual and legal situation of the undertakings favoured by the measure in question is comparable with that of those which are not (judgment of 8 November 2022, Fiat Chrysler Finance Europe v Commission, C‑885/19 P and C‑898/19 P, EU:C:2022:859, paragraph 69 and the case-law cited).

37 For the purposes of assessing the selective nature of a tax measure, it is, therefore, necessary that the common tax regime or the reference system applicable in the Member State concerned be correctly identified in the Commission decision and examined by the court hearing a dispute concerning that identification. Since the determination of the reference system constitutes the starting point for the comparative examination to be carried out in the context of the assessment of selectivity, an error made in that determination necessarily vitiates the whole of the analysis of the condition relating to selectivity (judgment of 8 November 2022, Fiat Chrysler Finance Europe v Commission, C‑885/19 P and C‑898/19 P, EU:C:2022:859, paragraph 71 and the case-law cited).

38 In that context, it must be stated, in the first place, that the determination of the reference framework, which must be carried out following an exchange of arguments with the Member State concerned, must follow from an objective examination of the content, the structure and the specific effects of the applicable rules under the national law of that State (judgment of 8 November 2022, Fiat Chrysler Finance Europe v Commission, C‑885/19 P and C‑898/19 P, EU:C:2022:859, paragraph 72 and the case-law cited).

39 In the second place, outside the spheres in which EU tax law has been harmonised, it is the Member State concerned which determines, by exercising its own competence in the matter of direct taxation and with due regard for its fiscal autonomy, the characteristics constituting the tax, which define, in principle, the reference system or the ‘normal’ tax regime, from which it is necessary to analyse the condition relating to selectivity. This includes, in particular, the determination of the basis of assessment, the taxable event and any exemptions that may apply (see, to that effect, judgment of 8 November 2022, Fiat Chrysler Finance Europe v Commission, C‑885/19 P and C‑898/19 P, EU:C:2022:859, paragraph 73 and the case-law cited).

40 It follows that only the national law applicable in the Member State concerned must be taken into account in order to identify the reference system for direct taxation, that identification being itself an essential prerequisite for assessing not only the existence of an advantage, but also whether it is selective in nature (judgment of 8 November 2022, Fiat Chrysler Finance Europe v Commission, C‑885/19 P and C‑898/19 P, EU:C:2022:859, paragraph 74).

41 The present case, in common with the case that gave rise to the judgment of 8 November 2022, Fiat Chrysler Finance Europe v Commission (C‑885/19 P and C‑898/19 P, EU:C:2022:859), concerns the question of the legality of a tax ruling adopted by the Luxembourg tax administration and based on the determination of the transfer price in the light of the arm’s length principle.

42 It is clear from that judgment, in the first place, that the arm’s length principle can only be applied if it is recognised by the national law concerned and in accordance with the detailed rules defined by it. In other words, as EU law currently stands, there is no autonomous arm’s length principle that applies independently of the incorporation of that principle into national law for the purposes of examining tax measures in the context of the application of Article 107(1) TFEU (see, to that effect, judgment of 8 November 2022, Fiat Chrysler Finance Europe v Commission, C‑885/19 P and C‑898/19 P, EU:C:2022:859, paragraph 104).

43 On that matter, the Court held that, while the national law applicable to companies in Luxembourg is intended, as regards the taxation of integrated companies, to bring about a reliable approximation of the market price and while that objective corresponds, in general terms, to that of the arm’s length principle, the fact remains that, in the absence of harmonisation in EU law, the specific detailed rules for the application of that principle are defined by national law and must be taken into account in order to identify the reference framework for the purposes of determining the existence of a selective advantage (judgment of 8 November 2022, Fiat Chrysler Finance Europe v Commission, C‑885/19 P and C‑898/19 P, EU:C:2022:859, paragraph 93).

44 In the second place, it must be recalled that the OECD Guidelines are not binding on the member States of that organisation. As the Court pointed out, even if many national tax authorities are guided by those guidelines in the preparation and control of transfer prices, it is only the national provisions that are relevant for the purposes of analysing whether particular transactions must be examined in the light of the arm’s length principle and, if so, whether or not transfer prices, which form the basis of a taxpayer’s taxable income and its allocation among the States concerned, deviate from an arm’s length outcome. Parameters and rules external to the national tax system at issue, such as the OECD Guidelines, cannot be taken into account in the examination of the existence of a selective tax advantage as provided for in Article 107(1) TFEU and for the purposes of establishing the tax burden that should normally be borne by an undertaking, unless that national tax system makes explicit reference to them (see, to that effect, judgment of 8 November 2022, Fiat Chrysler Finance Europe v Commission, C‑885/19 P and C‑898/19 P, EU:C:2022:859, paragraph 96).

45 In this case, it must be stressed that, in paragraphs 121 and 122 of the judgment under appeal, the General Court held as follows:

‘121 It should also be noted that when the Commission uses the arm’s length principle to check whether the taxable profit of an integrated undertaking pursuant to a tax measure corresponds to a reliable approximation of a taxable profit generated under market conditions, the Commission can identify an advantage within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU only if the variation between the two comparables goes beyond the inaccuracies inherent in the methodology used to obtain that approximation (judgment of 24 September 2019, Netherlands and Others v Commission, T‑760/15 and T‑636/16, EU:T:2019:669, paragraph 152).

122 Even though the Commission cannot be formally bound by the OECD Guidelines, the fact remains that those guidelines are based on important work carried out by groups of renowned experts, that they reflect the international consensus achieved with regard to transfer pricing and that they thus have a certain practical significance in the interpretation of issues relating to transfer pricing (judgment of 24 September 2019, Netherlands and Others v Commission, T‑760/15 and T‑636/16, EU:T:2019:669, paragraph 155).’

46 It follows from paragraph 121 of the judgment under appeal that, in finding that the Commission could, in a general manner, apply the arm’s length principle in the context of implementing Article 107(1) TFEU, even though that principle has no autonomous existence in EU law, without stating that that institution was required, as a preliminary step, to satisfy itself that that principle was incorporated into the national tax law concerned, in the present case Luxembourg tax law, and that express reference was made to it as such in that law, the General Court committed a first error of law. That error is not remedied by the fact that the General Court, in paragraph 137 of the judgment under appeal, considered, moreover wrongly, for the reasons set out in paragraphs 54 and 55 of the present judgment, that Luxembourg law enshrined that principle at the time of the facts of the case.

47 Likewise, by stating, in paragraph 122 of the judgment under appeal, that, despite their lack of binding force for the Commission, the OECD Guidelines have a ‘certain practical significance’ in the assessment of whether that principle has been observed, the General Court failed to recall that those guidelines were also not binding on the member States of the OECD and that, therefore, they have practical importance only to the extent that the tax law of the Member State concerned makes explicit reference to them. Hence, it did not review whether the Commission had satisfied itself that that was actually the case in Luxembourg tax law and the General Court itself took for granted that those guidelines applied, thus committing a second error of law.

48 It follows that, although moreover Ireland had submitted, as is clear from paragraph 132 of the judgment under appeal, that the arm’s length principle lacked any foundation in EU law, the General Court, which dismissed that argument as inadmissible and consequently did not examine it, whilst, on the substance, it put at issue the accuracy of the reference system used by the Commission in order to determine normal taxation and, consequently, whether there was an advantage for the benefit of the Amazon group, upheld an interpretation of the arm’s length principle contrary to EU law, as recalled, in particular in paragraphs 96 and 104 of the judgment of 8 November 2022, Fiat Chrysler Finance Europe v Commission (C‑885/19 P and C‑898/19 P, EU:C:2022:859) and thus wrongly confirmed the Commission’s determination of the reference system.

49 The whole of the General Court’s analysis in paragraphs 162 to 251, 257 to 295, 314 to 442 and 499 to 538 of the judgment under appeal, in so far as it concerns the condition of the existence of a selective advantage within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU, is based on the application, for the purposes of determining whether there is such an advantage, of the arm’s length principle pursuant to the OECD Guidelines irrespective of the incorporation of that principle into Luxembourg law.

50 Consequently, since it rests on an incorrect determination, by the General Court, of the relevant reference system for the purpose of determining whether there is a selective advantage within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU, that analysis is, in accordance with the case-law referred to in paragraph 37 of the present judgment, also incorrect.

51 It should however be recalled that, if the grounds of a judgment of the General Court disclose an infringement of EU law but its operative part is shown to be well founded on other legal grounds, such an infringement cannot lead to the setting aside of that judgment, and a substitution of grounds must be made and the appeal dismissed (see, to that effect, judgments of 25 March 2021, Xellia Pharmaceuticals and Alpharma v Commission, C‑611/16 P, EU:C:2021:245, paragraph 149, and of 24 March 2022, PJ and PC v EUIPO, C‑529/18 P and C‑531/18 P, EU:C:2022:218, paragraph 75 and the case-law cited).

52 That is the case here.

53 First, the Commission applied the arm’s length principle as if it had been recognised as such in EU law, as is shown, inter alia, in recitals 402, 403, 409, 519, 520 and 561 of the decision at issue. However, it is clear from paragraph 104 of the judgment of 8 November 2022, Fiat Chrysler Finance Europe v Commission (C‑885/19 P and C‑898/19 P, EU:C:2022:859), that, as EU law currently stands, there is no autonomous arm’s length principle that applies independently of the incorporation of that principle into national law.

54 Secondly, it considered, as is clear from recitals 241 and 242 of the decision at issue, that Article 164(3) of the Law on income tax was interpreted by the Luxembourg tax administration as enshrining the arm’s length principle in Luxembourg tax law. However, as is clear from paragraphs 96 and 104 of the judgment of 8 November 2022, Fiat Chrysler Finance Europe v Commission (C‑885/19 P and C‑898/19 P, EU:C:2022:859), only the incorporation of that principle as such into national law, which as a minimum requires that that law refer explicitly to that principle, would permit the Commission to apply it in the determination of the existence of a selective advantage within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU.

55 As the Commission itself recognised in recital 243 of the decision at issue, it is only since 1 January 2017, namely after the adoption and extension of the tax ruling at issue, that a new article of the Law on income tax ‘explicitly formalises the application of the arm’s length principle under Luxembourg tax law’. It is therefore established that the requirement recalled by the case-law cited in the preceding paragraph was not satisfied at the time of adoption, by the Member State concerned, of the measure that the Commission found to be State aid, such that that institution could not apply that principle retroactively in the decision at issue.

56 Thirdly, by applying, in recital 246 et seq. of that decision, the OECD Guidelines on transfer pricing without having demonstrated that they had been, wholly or in part, explicitly adopted in Luxembourg law, the Commission breached the prohibition, recalled in paragraph 96 of the judgment of 8 November 2022, Fiat Chrysler Finance Europe v Commission (C‑885/19 P and C‑898/19 P, EU:C:2022:859), on taking into account, in the examination of the existence of a selective tax advantage within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU and for the purposes of establishing the tax burden that should normally be borne by an undertaking, parameters and rules external to the national tax system at issue, such as those guidelines, unless that national tax system makes explicit reference to them.

57 It should be recalled, in that regard, that such errors in determining the rules actually applicable under the relevant national law and, therefore, in identifying the ‘normal’ taxation in the light of which the tax ruling at issue had to be assessed necessarily invalidate the entirety of the reasoning relating to the existence of a selective advantage (judgment of 8 November 2022, Fiat Chrysler Finance Europe v Commission, C‑885/19 P and C‑898/19 P, EU:C:2022:859, paragraph 71 and the case-law cited).

58 It follows from all those considerations that the General Court was fully entitled to find, in paragraph 590 of the judgment under appeal, that the Commission had not established the existence of an advantage for the benefit of the Amazon group, within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU, and to annul, therefore, the decision at issue.

59 In the light of the foregoing and on the basis of a substitution of grounds in accordance with the case-law cited in paragraph 51 of the present judgment, it is necessary to reject the two grounds of appeal and, therefore, to dismiss the appeal in its entirety.

Costs

60 In accordance with Article 184(2) of the Rules of Procedure of the Court of Justice, where the appeal is unfounded, the Court shall make a decision as to the costs.

61 Under Article 138(1) of those rules, which applies to appeal proceedings by virtue of Article 184(1) thereof, the unsuccessful party is to be ordered to pay the costs if they have been applied for in the successful party’s pleadings.

62 In the present case, since the Commission has been unsuccessful, it must be ordered to bear, in addition to its own costs, those incurred by the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and Amazon, in accordance with the forms of order sought by the appellants.

63 In addition, Article 140(1) of the Rules of Procedure, which is also applicable to appeal proceedings by virtue of Article 184(1) thereof, provides that the Member States and institutions which have intervened in the proceedings are to bear their own costs. Ireland, which has intervened, must therefore bear its own costs.

On those grounds, the Court (Second Chamber) hereby:

1. Dismisses the appeal;

2. Orders the European Commission to bear, in addition to its own costs, those incurred by the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, Amazon.com Inc. and Amazon EU Sàrl;

3. Orders Ireland to bear its own costs.

Copyright – internationaltaxplaza.info

Follow International Tax Plaza on Twitter (@IntTaxPlaza)