On March 21, 2024 on the website of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) the opinion of Advocate General Collins in the Case C‑39/23, Keva, Landskapet Ålands pensionsfond and Kyrkans Centralfond versus Skatteverket, ECLI:EU:C:2024:265, was published.

Facts and the questions referred for a preliminary ruling

1. In Sweden there are three types of pension: (1) the national public pension, (2) occupational pensions, and (3) private pensions. Employers and employees are required to make statutory contributions, calculated by reference to the latters’ earnings, in order to finance the national public pension. Those annual contributions fund the payment of pensions in that year. Where in a given year payments-in exceed payments-out, the general pension funds manage the excess. Conversely, in a year when payments-in are lower than payments-out, the GP funds cover any deficit. The GP funds thus act as a buffer and stabiliser for the national public pension system. Payment of the national public pension is the responsibility of the Pensionsmyndigheten (Pensions Agency, Sweden), not the GP funds.

2. The Swedish State is exempt from all tax obligations. Since the GP funds are an integral part of the State, they are exempt from paying tax on the dividends that they receive from companies resident in Sweden.

3. In Finland, the law requires all employees to enrol in an occupational pension scheme. Those schemes are financed principally by contributions from employers and employees.

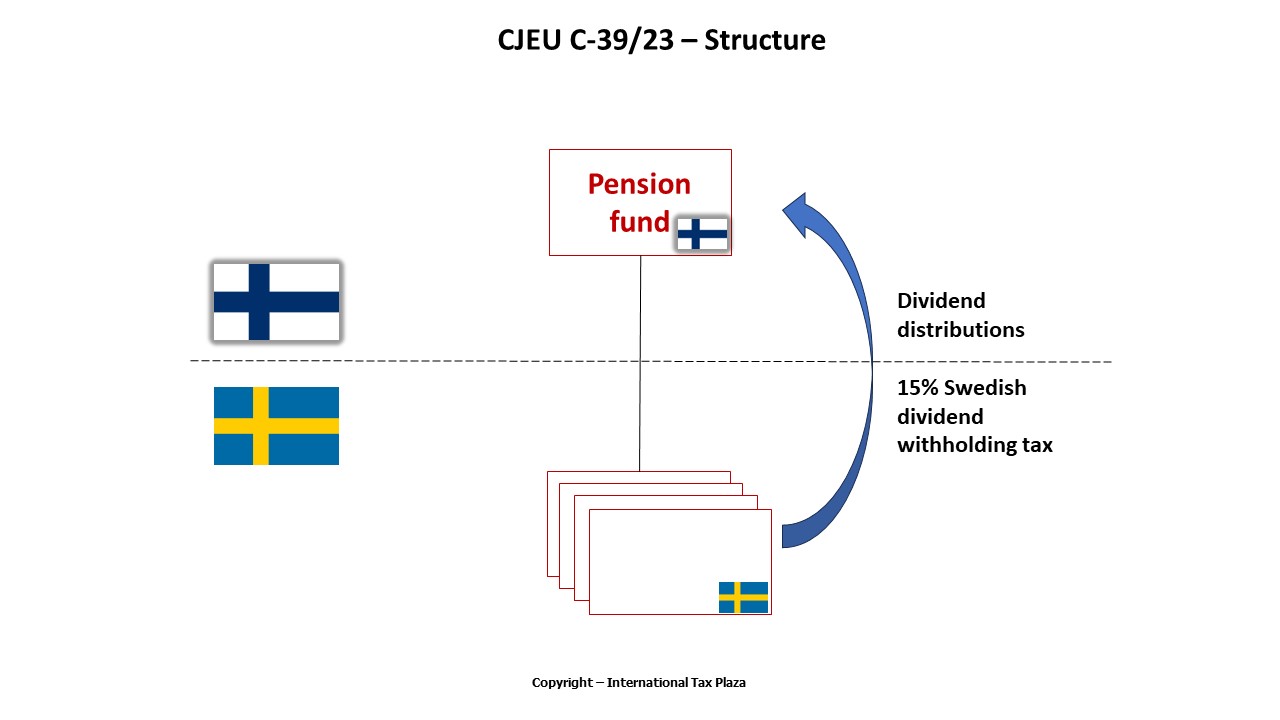

4. Keva, Landskapet Ålands pensionsfond and Kyrkans Centralfond (‘the applicants’) are among the institutions that operate the occupational pension system in Finland. Keva is a legal person governed by public law and is tax-exempt in Finland. It administers the occupational pensions of employees of, inter alia, local government and State authorities, the Evangelical Lutheran Church and the Bank of Finland. Its principal task is to manage funds so as to guarantee the payment of pensions and to stabilise the evolution of pension contributions. Keva collects contributions and pays out pensions. Landskapet Ålands pensionsfond is the pension fund of the Åland region and is an integral part of that region’s administration. It is responsible for the management of occupational pensions on behalf of the Åland region’s employees. Its principal task is to manage its capital, which is kept separate from the region’s budget. Landskapet Ålands pensionsfond does not pay out pensions. It is partially exempt from tax in Finland and does not pay tax on dividends received from limited companies resident in that Member State. Kyrkans Centralfond is part of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland. Until 1 January 2016, it managed the pension fund for its employees as part of its general responsibility for the management of Church funds. Kyrkans Centralfond is, in practice, exempt from income tax in Finland. Keva managed the payment of pensions for Kyrkans Centralfond.

5. Between 2003 and 2016, the applicants received dividends from companies resident in Sweden. Pursuant to Articles 1, 4 and 5 of the kupongskattelagen (1970:624) (Law (1970:624) on the taxation of dividends), foreign legal persons in receipt of share dividends from companies resident in Sweden pay withholding tax at the rate of 30%. That rate of tax is reduced to 15% for legal persons resident in the states party to the multilateral double taxation agreement between Denmark, the Faroe Islands, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden. Because the applicants are exempt from paying tax on dividends in Finland, they were unable to deduct the withholding tax that they had paid in Sweden from any tax liabilities that they might have had in Finland. As a consequence, the withholding tax on the dividends that they received in Sweden became final.

6. The applicants sought repayment of the tax that the Skatteverket (‘the respondent’) had deducted from the dividends that they had received from companies resident in Sweden. The applicants claimed that their circumstances were comparable to those of the GP funds. They therefore argued that the difference in the tax treatment of the dividends they received and those the GP funds received was contrary to Article 63 TFEU. The respondent rejected that argument on the ground that the applicants’ circumstances were not objectively comparable to those of the GP funds.

7. The applicants challenged the validity of that decision by way of an action before the Förvaltningsrätten i Falun (Administrative Court, Falun, Sweden), which rejected their claim. The Kammarrätten i Sundsvall (Administrative Court of Appeal, Sundsvall, Sweden) rejected the applicants’ appeal against that judgment.

8. The applicants brought an appeal on a point of law before the Högsta förvaltningsdomstolen (Supreme Administrative Court, Sweden), the referring court. That court heard that appeal in so far as it raised the question as to whether the levying of a withholding tax on dividends received by a public pension institution established in Finland is compatible with the free movement of capital under EU law in circumstances where corresponding dividends that the GP funds receive are not taxed. In that context, the Högsta förvaltningsdomstolen (Supreme Administrative Court) decided to stay the proceedings and to refer the following questions to the Court of Justice for a preliminary ruling:

‘(1) Does the fact that dividends paid by domestic companies to foreign public pension institutions are subject to withholding tax, whereas the corresponding dividends are not taxed if they accrue to the [source] State through its general pension funds, constitute such negative differential treatment that it entails a restriction of the free movement of capital prohibited, in principle, by Article 63 TFEU?

(2) If Question 1 is answered in the affirmative, what are the criteria that should be taken into account when assessing whether a foreign public pension institution is in a situation which is objectively comparable to that of the [source] State and its general pension funds?

(3) Can a possible restriction be regarded as being justified by overriding reasons of public interest?’

9. The applicants, the respondent, the Spanish and Swedish Governments and the European Commission submitted written observations. At the hearing of 11 January 2024, they presented oral argument and replied to the Court’s questions.

The conclusion of the Advocate General

In the light of all the foregoing considerations, Advocate General Collins proposes that the Court answer the questions referred for a preliminary ruling by the Högsta förvaltningsdomstolen (Supreme Administrative Court, Sweden) as follows:

Article 63 TFEU must be interpreted as meaning that

– the fact that dividends paid by domestic companies to foreign public pension institutions are subject to withholding tax, whereas the corresponding dividends are not taxed if they accrue to the source State through its general pensions funds, constitutes such negative differential treatment that it entails, in principle, a restriction of the free movement of capital;

– the criteria to be taken into account when assessing whether a foreign public pension institution is in a situation that is objectively comparable to that of the source State and its general pension funds must include their respective purposes, functions and core tasks, the regulatory frameworks in which they operate and the characteristics of their organisations;

– whilst a potential restriction on the free movement of capital may be justified by reliance upon overriding reasons in the public interest, the justifications that have been advanced here do not, in principle, appear to constitute overriding reasons of public interest.

From the assessment made by the Advocate General

A. The first question

1. Parties’ observations

10. The applicants and the Commission are of the view that, since dividends that non-resident pension funds received from companies resident in Sweden were subject to what is effectively a final withholding tax, whilst dividends the GP funds received from those same companies are tax‑exempt, the former are likely to be discouraged from investing in Sweden, thereby giving rise to a restriction on the free movement of capital prohibited by Article 63 TFEU.

11. The respondent and the Spanish and Swedish Governments submit that the difference in the tax treatment of dividends received by resident and non-resident public pension funds is not a restriction on the free movement of capital. That difference in treatment arises by reason of the fact that the GP funds are an integral part of the Swedish State, and not because of their place of residence. The respondent further observes that the GP funds are the only tax‑exempt pension funds in Sweden. Dividends received by pension funds resident in Sweden, other than the GP funds, are subject to a yield tax, whilst dividends received by non-resident pension funds are subject to a withholding tax. The respondent and the Swedish Government add that the exemption of the GP funds from taxation by reason of their integration into the State confers no economic advantage on either those funds or on the Swedish State. It follows that any difference in the tax treatment of the GP funds does not discourage public pension funds resident in other Member States from investing in Sweden. According to the Swedish Government, to hold otherwise would have the effect of obliging Member States to contribute towards financing general old-age pensions in other Member States. That obligation does not exist since each Member State is responsible for financing its own national public pension system. The existence of that obligation would also be contrary to Article 153(1) and (4) TFEU. In the absence of harmonisation of EU law in the field of social security, each Member State is entitled to design and to organise its social security system, including the manner by which it is financed. The Swedish Government finally observes that national public pension systems do not compete with each other since, by virtue of the coordination of Member States’ social security systems, a person may benefit from the compulsory old-age pension scheme of only one Member State at any time.

2. Analysis

12. By way of introduction, it may be observed that, whilst Article 63 TFEU prohibits all restrictions on the free movement of capital between Member States and between Member States and third countries, Member States retain the right to apply relevant provisions of their tax law that distinguish between taxpayers that are not in the same situation with regard to their place of residence or with regard to the place where their capital is invested. For that difference in treatment to be compatible with the Treaty provisions governing the free movement of capital, it must apply to situations that are not objectively comparable or be justified by an overriding reason in the public interest.

13. Article 63(1) TFEU prohibits measures that discourage non-residents from making investments in a Member State or discourage that Member State’s residents from investing in other Member States. In order to establish, in principle, the presence of such a restriction, it is sufficient to show that the tax treatment of dividends that non-resident public pension funds receive from companies resident in Sweden is liable to discourage those institutions from investing in that Member State. Where a Member State treats dividends received by non-resident pension funds less favourably than dividends received by resident pension funds, the Court has held that that difference in treatment is liable to deter investors established in other Member States from investing in that Member State, thereby constituting a restriction on the free movement of capital. The Court has also held that the imposition of a heavier tax burden on dividends received by non-resident pension funds than that charged on the same dividends received by resident pension funds constitutes less favourable treatment. The dividends the applicants received from companies resident in Sweden were subject to a final withholding tax at a rate of 15%, whilst the same dividends were exempt from tax when the GP funds received them. That the tax treatment of the Swedish State does not constitute preferential treatment of either it or of its public pension funds has no bearing upon whether that treatment constitutes a restriction on the free movement of capital. It is the negative impact of the measure upon investment from other Member States that alone determines whether it constitutes such a restriction.

14. It follows that the difference in the tax treatment of dividends that the applicants receive from companies resident in Sweden, as compared with the tax treatment of dividends the GP funds receive, constitutes, in principle, a restriction of the free movement of capital that Article 63 TFEU prohibits.

15. Article 153(1) and (4) TFEU provides that the European Union shall support and complement Member State activities in the fields of, inter alia, social security and the social protection of workers. Any provisions the European Union adopts under that article are to affect neither the right of Member States to define the fundamental provisions of their social security systems, nor the financial equilibrium of those systems. The limitations on the exercise of the European Union’s competence in that field apply, by their very nature, to the exercise of that competence and do not govern the application of rules contained in primary law. The Swedish Government does not identify any provisions the European Union has adopted under Article 153 TFEU that might affect its right to define the fundamental provisions of its social security system or affect that system’s financial equilibrium significantly. For these reasons, the arguments that the Swedish Government advances under this rubric must be dismissed.

16. The Swedish Government’s other arguments by reference to the state of harmonisation and the nature of the co-ordination of social security systems at the EU level similarly have no bearing on the question as to whether a difference between the tax treatment of the GP funds and those resident in other Member States constitutes a restriction for the purposes of Article 63 TFEU. Member States must comply with Treaty provisions, including those governing the four freedoms, irrespective of whether EU law does or does not impose an obligation on Member States to contribute towards financing other Member States’ social security systems.

17. In the light of the foregoing, I propose that the Court answer the first question as follows:

Article 63 TFEU must be interpreted as meaning that the fact that dividends paid by domestic companies to foreign public pension institutions are subject to withholding tax, whereas the corresponding dividends are not taxed if they accrue to the source State through its general pension funds, constitutes such negative differential treatment that it entails, in principle, a restriction of the free movement of capital.

B. The second question

1. Parties’ observations

18. The applicants and the Commission contend that the applicants’ circumstances and those of the GP funds are objectively comparable. When assessing whether a foreign public pension institution is in an objectively comparable situation to that of a domestic pension fund, the applicants submit that regard should be had to the purpose, functions and core tasks of the bodies under comparison. The applicants assert that they exist for the same purposes as the GP funds: as buffer funds engaged in the management and the maintenance of their respective compulsory occupational pension insurance systems. Since they serve an identical purpose, the applicants claim that it is unnecessary for them to take an identical legal form as the GP funds in order for them to be regarded as objectively comparable. In any event, whilst the GP funds are part of the Swedish State, the applicants are part of the Finnish State for all practical purposes.

19. A number of factors demonstrate that the Finnish and Swedish public pension funds are objectively comparable. They are both governed by specific laws. Compulsory public pension contributions are paid to the GP funds in Sweden, whilst in Finland such contributions are paid to Keva and to the Landskapet Ålands pensionsfond. The Pensionsmyndigheten (Pensions Agency, Sweden) pays out pensions in Sweden, whilst Keva (on its own behalf and on behalf of the Kyrkans Centralfond) and the government of the Åland region (on behalf of Landskapet Ålands pensionsfond) perform that function in Finland. The GP funds and the applicants are among the largest institutional investors in their respective Member States. Operating within a strict legal framework and being subject to precise investment strategies, the GP funds and the applicants invest in, inter alia, domestic and foreign companies, property and financial instruments. Their tax treatment in their Member States of residence is also identical since the GP funds are not subject to tax in Sweden because they are part of the Swedish State, whilst the applicants are exempt from income tax in Finland by law.

20. The Commission observes that the Swedish and Finnish pension funds serve the same aim and social purpose and have the same organisational and legal structures. Their operation, including their financing models are, in practice, identical. Just as the GP funds are part of the Swedish State, Landskapet Ålands pensionsfond and Kyrkans Centralfond are, respectively, part of the region of Åland and of the Evangelical Lutheran Church. Whilst Keva is a legal entity governed by public law, that does not preclude it from being comparable to the GP funds. Comparability is to be assessed in the round, taking into account the aims, functions and activities of the institutions under examination.

21. The respondent and the Spanish and Swedish Governments assert that the GP funds and the applicants are not in objectively comparable circumstances. The difference in the tax treatment of the GP funds and the applicants is a consequence of the fact that the former is part of the State, and not because they are resident in Sweden. The respondent further observes that the GP funds operate as a buffer in the Swedish national public pension system. As stabilisation funds, their aim is to promote the financial stability and durability of the Swedish social security system. Non-resident public pension funds cannot, by definition, pursue that particular aim.

22. The Swedish Government contends that the aims a tax measure pursues may be limited to circumstances and matters of public interest that are linked directly to a given Member State. As a result, cross-border and internal situations are not objectively comparable. The exemption from taxation afforded to the GP funds is directly linked to the Swedish State because it seeks to avoid the administrative burden of a circular flow of resources that is of no financial benefit to the State.

23. In the view of the Swedish Government, the entitlement of each Member State to design and to organise its social security system, including the manner whereby it is financed, is relevant to the assessment of objective comparability. The public interest that the national public pension system promotes is directly linked to the Swedish State and does not compete with systems that exist in other Member States. It is therefore not possible to objectively compare the various public pension systems in the Member States.

24. If, quod non, it is possible to assess the objective comparability of the applicants and the GP funds, the Swedish Government and the respondent accept that regard should be had to their respective purposes, functions and core tasks, the regulatory framework within which they operate, the methods whereby they are financed and the manner in which they are organised. The Swedish Government nevertheless insists that, in making that assessment, account should be taken of the independence of a non-resident public pension fund from any responsibility for other social security benefits and from the national budget. Objective comparability ought to require that the non-resident public pension fund is concerned solely and exclusively with the management of buffer funds with a view to ensuring the availability of old-age pensions. Such funds should also be entirely tax‑exempt under national law. The ultimate assessment of these matters is a matter for the referring court.

2. Analysis

25. Differences in treatment afforded by national tax legislation may be compatible with the Treaty provisions governing the free movement of capital where that difference applies to situations that are not objectively comparable. It is clear from the Court’s case-law that comparability must be examined having regard to the aim, purpose and content of the national provisions under scrutiny. When determining whether a difference in treatment that results from legislation reflects the presence of an objectively different situation, account is to be taken of the relevant distinguishing criteria contained in that legislation.

26. Once a Member State, either unilaterally or by way of a convention, imposes a charge to tax on dividend income that resident and non-resident taxpayers receive from a resident company, the situation of those taxpayers is comparable. For the reasons given in points 21 to 23 of the present Opinion, the respondent and the Spanish and Swedish Governments assert that the applicants and the GP funds are not objectively comparable.

27. Subject to verification by the referring court, there appears to be nothing to suggest that, having regard to the aim, purpose and content of the exemption of the Swedish State from taxation, that exemption was designed to reflect an objective difference in the circumstances of resident and non-resident public pension funds. This accords with the assertion by the respondent and the Spanish and Swedish Governments that the difference in treatment arises by reason of the fact that the GP funds are an integral part of the Swedish State and is not based on residence. It appears from the information before the Court that the decision to exempt the Swedish State from tax was introduced in order to avoid the administrative burden of a circular flow of resources that is of no financial benefit to that State. Consequently, it may be observed that instead of reflecting a difference in the respective circumstances of the applicants and the GP funds, the exemption afforded to the latter creates such a difference.

28. Although the aim, purpose and content of the exemption of the Swedish State from tax does not suggest any criteria that may assist in an objective comparison of the applicants and the GP funds, the parties are, nevertheless, agreed on some of the criteria to be taken into account when carrying out that exercise.

29. A finding that persons are in objectively comparable circumstances such that they are to be treated in the same manner for the purposes of applying Article 63 TFEU does not equate to a finding that they are in identical circumstances. An overall assessment of the objective comparability of the applicants and of the GP funds requires having regard to their respective purpose, functions and core tasks, the regulatory frameworks in which they operate and the principal characteristics of their organisations. It follows that ancillary matters, including differences of a purely technical nature, are not determinative of that assessment.

30. Seen in that light, the respondent’s assertion that non-resident public pension funds do not aim at promoting the financial stability and durability of the Swedish social security system and that they therefore cannot be compared to the GP funds is unduly restrictive. Since by definition each fund has the purpose of protecting the stability and durability of a distinct national pension system, such an approach would make it impossible to compare even identical pension funds across frontiers. The assessment of the aims the applicants pursue can be made only in the context of the social security system in which they operate, and not by reference to that of another Member State.

31. In the light of the foregoing considerations, I propose that the Court answer the second question as follows:

Article 63 TFEU must be interpreted as meaning that the criteria to be taken into account when assessing whether a foreign public pension institution is in a situation that is objectively comparable to that of the source State and its general pension funds must include their respective purposes, functions and core tasks, the regulatory frameworks in which they operate and the characteristics of their organisations.

C. The third question

32. The third question asks if a restriction on the free movement of capital can be justified by overriding reasons of public interest. As formulated, that question can only admit of an affirmative answer. Read in the context in which the order for reference was made, it is clear that the referring court seeks guidance as to whether the justifications advanced for a potential restriction on the free movement of capital are, in principle, capable of constituting overriding reasons of public interest. I therefore propose that the Court answer the third question as so reformulated.

1. Parties’ observations

33. The applicants and the Commission contend that no overriding reason in the public interest has been advanced that is capable of justifying the restriction on the free movement of capital that they identify in the different tax treatment of the applicants as compared to that afforded to the GP funds. Neither any apprehended loss of income to the GP funds as a consequence of levying tax on the dividends they receive, nor any difficulties of an administrative nature, justify the existence of that restriction. According to the Commission, it is a matter for Sweden should it wish to allocate resources to the GP funds in the event that dividends they receive were to be liable to tax. Nor is there anything to prevent Sweden from exempting objectively comparable public pension funds from taxation, as it has already done with respect to pension funds resident in Canada and in the United States of America.

34. If the tax treatment at issue constitutes a restriction on the free movement of capital, the respondent and the Spanish and Swedish Governments submit that that restriction may be justified by reference to overriding reasons in the public interest. The respondent and the Swedish Government submit that the purpose of the GP funds is to guarantee the financing of Sweden’s social policy by ensuring that it is financially independent of, and separate from, the rest of the State budget. As matters stand, the Swedish State is not required to allocate resources to the GP funds to offset the payment of tax on dividends from their own resources. That arrangement maintains public confidence in the pension system.

35. The respondent observes that the principle of fiscal territoriality and the balanced allocation of powers of taxation between Member States accords to them the right to tax income generated on their respective territories. To tax dividends received by the GP funds would impose an unnecessary administrative burden without creating any financial benefit for the State. In contrast, to exempt the applicants from taxation on dividends they received from Swedish resident companies would cause the Swedish State to suffer a loss.

36. The Swedish Government further submits that it would be contrary to the balanced allocation of powers between the Member States in the field of social security to require Sweden to extend the benefit of the tax exemption that it affords to the GP funds to public pension funds established in other Member States.

37. Whilst acknowledging that grounds of a purely economic or administrative nature do not constitute overriding reasons in the public interest that are capable of justifying a restriction on the exercise of a fundamental freedom guaranteed by the Treaties, both the Swedish Government and the respondent contend that a restriction may be justified when it is dictated by reasons of an economic nature taken in pursuit of a public interest objective. In that regard, the Swedish Government asserts that account must be taken of the reasons that underpin the design of the national public pension system and the need to guarantee the independence, financial stability and durability of the GP funds.

2. Analysis

38. According to the Court’s settled case-law, restrictions on the free movement of capital are permissible where they are justified by overriding reasons in the public interest, are suitable to attain those objectives and do not go beyond what is necessary for that purpose. Invoking overriding reasons in the public interest exists only to the extent that such interests are not protected by EU harmonisation measures. In the absence of such harmonisation measures it is, in principle, for the Member States to decide on the degree of protection that they wish to afford to those interests and the manner whereby that level of protection may be attained. Such measures must nevertheless remain within the limits the Treaty sets and be proportionate.

39. Overriding reasons in the public interest include ensuring the effectiveness of fiscal supervision and combating tax evasion, preventing wholly artificial arrangements, preserving the coherence of tax systems and balancing the allocation of the power to tax in relations between Member States and third countries.

40. Subject to verification by the referring court, it appears that the purpose of relieving the Swedish State of the obligation to pay income tax is to avoid the administrative burden of a circular flow of resources that is of no financial benefit to that State. Such a justification is in the nature of an administrative convenience. As the Commission rightly observes, administrative convenience is not an overriding reason in the public interest and cannot justify a failure to comply with Treaty obligations. That observation applies equally to the argument that the GP funds must be kept independent of, and separate from, the rest of the State budget in order to maintain public confidence in those funds. As for the assertion that to tax dividends the GP funds receive would require the Swedish Government to allocate resources to them in order to alleviate the consequences of paying that tax, I agree with the Commission’s suggestion that it is ultimately a matter for Sweden to decide.

41. The Court has also held that where a Member State chooses to exempt completely or almost completely dividends received by resident pension funds, it cannot justify the taxation of dividends received by non-resident pension funds, as the Swedish Government seeks to do, by reference to a need to ensure a balanced allocation of the power to tax as between Member States and third countries. That rule must apply equally to any reliance upon the need to ensure a balanced allocation of the power to tax as between the Member States.

42. Even if each Member State is free to design and to organise its social security system, including the means as to how it is to be financed, the exercise of that freedom is subject to compliance with the Treaties. In its tax treatment of such funds, however, Sweden is bound not to treat non-resident public pension funds in such a manner as to create a restriction on the free movement of capital.

43. In so far as the Swedish Government asserts that the different tax treatment may be justified by reasons of an economic nature in the pursuit of an objective in the public interest, it has not adduced any elements or factors, beyond administrative convenience, to support that claim.

44. In the light of the above considerations, I propose that the Court answer the third question as follows:

Article 63 TFEU must be interpreted as meaning that whilst a potential restriction on the free movement of capital may be justified by reliance upon overriding reasons in the public interest, the justifications that have been advanced here do not, in principle, appear to constitute overriding reasons of public interest.

Copyright – internationaltaxplaza.info

Follow International Tax Plaza on Twitter (@IntTaxPlaza)