On July 22, 2022 a very interesting opinion of Dutch Advocate General Wattel was published on the website of the Dutch courts. In the underlying case the the Dutch Supreme Court is asked to answer the question if and under which conditions a so-called fiscal unity decree that was incorrectly issued by a Dutch tax inspector can be revised or withdrawn.

Facts

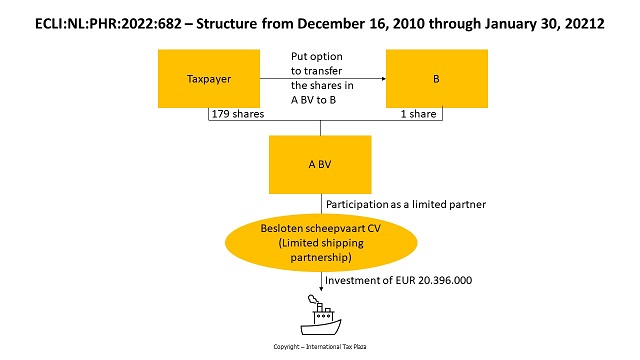

The taxpayer operates a wholesale business in building materials. On October 22, 2010 the taxpayer signed a term sheet committing her to invest in (apparently) a motor tanker (MT) (a ship). On November 5, 2010 the taxpayer concluded a participation agreement with [A] BV, which at that time was still under incorporation. In this participation agreement the terms of the aforementioned term sheet are worked out in more detail. On November 29, 2010 the taxpayer participated with 179 shares in [A] BV and a unrelated third-party [B] participated with 1 share in [A] BV. [A] BV on its turn participated in the besloten scheepvaart CV [C] (the CV) (a Limited shipping partnership). On December 16, 2010 the CV invested approximately € 20,396,000 in the vessel.

Upon a joint request filed by the taxpayer and [A], on March 21, 2011 the tax inspector issued a so-called fiscal unity decree in which he confirmed that as its date of incorporation [A] BV has been included into a fiscal unity, as referred to in art. 15 of the 1969 Dutch Corporate Income Tax Act, of which the taxpayer was the parent entity.

As parent entity of the fiscal unity, in 2011 the taxpayer requested the tax inspector to reduce its provisional corporate tax assessments that were issued for the years 2010 and 2011. The reason for this was request was that the taxpayer wanted to take an arbitrary depreciation into account with respect to its investment in the ship. The Inspector has granted that reduction.

Based on the term sheet and the participation agreement, [B] was obliged to make an irrevocable and unconditional offer for taxpayer’s shares in [A] on April 1, 2011 at a price that was to be determined in accordance with a formula (hereinafter referred to as: the put option). If at the end of 2012 the taxpayer was still a shareholder of [A], the taxpayer would be obliged to contribute another tranche of capital amounting to € 786.298 into the CV via [A]. (This second tranche comes next to the first tranche as described in the following paragraph)

On January 27, 2012 the taxpayer contributed an amount of € 824,000 as share premium in [A]. The taxpayer was obliged to do so on the basis of a tax sharing agreement. The amount of € 824,000 represents 53.75% of the tax benefit the taxpayer enjoyed from the arbitrary depreciation.

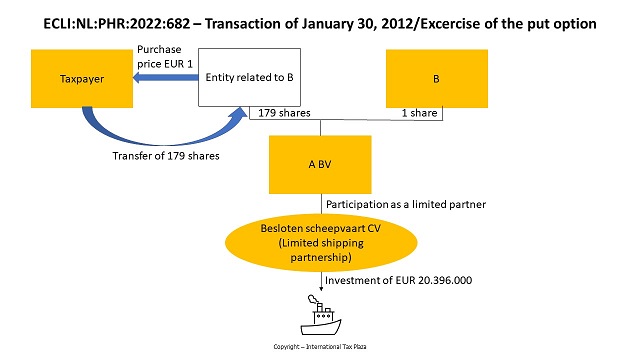

On January 30, 2012 the taxpayer exercised the put option by transferring its shares its [A] to an entity associated with [B] against a sales price of € 1. On June 30, 2014 the taxpayer requested the tax inspector to declare that the fiscal unity between the taxpayer and [A] ended/was broken-up as per December 14, 2012. The Inspector has thus stated.

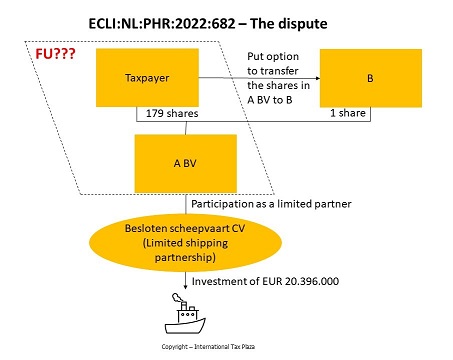

On October 29, 2015 the Inspector informed the taxpayer that as a result of a third party investigation undertaken to his opinion, the put option entailed that the value development of the shares [A] did not concern the taxpayer and that therefore the conditions for a fiscal unity were never met. Consequently the tax inspector was of the opinion that no fiscal unity had been established. Therefore the tax inspector issued an additional assessment for the year 2010 in which he reversed the arbitrary depreciation and revised the tax loss that had previously been established for 2010 (in the provisional corporate tax assessments that was issued for the year 2010).

The dispute

Parties are disputing whether the additional assessment was justifiably imposed and for the correct amount, and in particular whether (i) in 2010 a fiscal unity for Dutch corporate income tax purposes between the taxpayer and [A] existed in 2010, and (ii) there were grounds for the issuance of an additional assessment and the revision of the previously issued loss decision.

Legal context

Article 15, Paragraph 1 of the Dutch corporate income tax Act

Article 15, Paragraph 1 of the Dutch corporate income tax Act reads as follows:

“In the event that a taxpayer (parent company) owns the legal and economic ownership of at least 95 percent of the shares in the paid-up nominal capital of another taxpayer (subsidiary), at the request of both taxpayers the tax shall be levied on them as if there were one taxpayer, in the sense that the activities and assets of the subsidiary form part of the activities and assets of the parent company. The tax is levied at the level of parent company. In that case, the taxpayers together are regarded as a fiscal unity. More than one subsidiary may be part of a fiscal unity.”

The District Court

The District Court has ruled that a fiscal unity between the taxpayer and [A] BV never existed because the taxpayer was not the economic owner of the shares in [A] BV. In the opinion of the District Court the fact that a decree stating otherwise was wrongly issued does not change that. According to the District Court the option data that was not submitted when the request for a fiscal unity was filed constitute new facts pursuant to Article 16, Paragraph 1 of the General Tax Act and Article 20b, Paragraph 3 of the Dutch corporate income tax Act, so that the tax inspector cannot be blamed for official negligence.

The Court of Appeal

From the legislative history the Court concludes that the application procedure for a fiscal unity is intended to provide legal certainty. According to the Court and partly based on the official Instruction Withdrawal or Revision of Decrees, incorrect decrees in respect of which the law does not provide for a withdrawal or revision, such as the fiscal unity decree, cannot be revised to the detriment of the applicant for the sake of legal certainty, unless the applicant has intentionally or grossly negligently provided incorrect or incomplete information. According to the Court of Appeal, the taxpayer cannot be accused of being inaccurate or incomplete to such an extent that the taxpayer was grossly negligent. Therefore the tax inspector is bound by his decision until the moment that he announces that, in his view, the conditions to form a fiscal unity were not met. Because no such notification has been made in 2010, the taxpayer and [A] BV were members of the same fiscal unity in that year, so that the taxpayer (fiscal unity) could take an arbitrary depreciation over the investment in the ship into account in that year.

Pleas of the Secretary of State for Finances

The Secretary of State argues in cassation that the Court of Appeal wrongly ruled that:

(i) incorrect fiscal unity decrees in principle cannot be revised or withdrawn to the detriment of the taxpayer, although it appears from HR BNB 2015/131 that if the conditions are not met no fiscal unity is created despite the issuance of such a decree;

(ii) the legal certainty only yields if the decree was issued on the basis of incorrect or incomplete information in the application due to intent or gross negligence on the part of the applicant; and

(iii) the Instruction reflects policy on which taxpayers also can rely in when fiscal unity decrees are issued and based on which in the underlying case the tax inspector had a duty to investigate.

From the opinion of the Advocate General

The Advocate General has established that a fiscal unity (for Dutch corporate income tax purposes) will end by operation of law if no longer all legal conditions are met, so without any official action being needed. So logically a fiscal unity will not come into existence if not all the conditions are met. According to the Advocate General this does not change because an incorrect decree to the contrary has been issued (a decree stating that a fiscal unity came into existence). Revision or withdrawal of the fiscal unity decree is then not possible, because according to HR BNB 2022/64 the fact that a fiscal unity decree was issued does not mean that a fiscal unity was also established contra legem, but only that (i) if the conditions are met, the effective date of the fiscal unity is established (legal expectations) and (ii) that under certain circumstances it can arouse justified legal expectations contra legem. Such legal expectations were excluded in HR BNB 2015/131 because in that case it regarded a so-called anti-tax scheme. In the underlying case, the reliance on confidence in the decree cannot be ruled out, since the Court of Appeal has established the absence of bad faith.

It therefore comes down to the yardstick for assessing the reliance on confidence. The Court did not apply the doctrine of legitimate expectations, nor did it apply the doctrine of recovery of unpaid taxes, but a rule of law which in the view of the Court of Appeal exists and that in its view arranges that decrees that are issued upon request of a taxpayer and which revision or withdrawal is not regulated by law, cannot be revised or withdrawn except in cases of bad faith. According to the Advocate General such legal rule does not exist, but according to him the question whether this is the case is irrelevant in the underlying case because it follows from HR BNB 2022/64 that the doctrine of legal expectations must be applied: a fiscal unity decree is a conscious position statement by the tax inspector that is legally to be respected can lead to the legal expectation that a fiscal unity exists if:

(i) the taxpayer could reasonably assume that the tax inspector had or could have taken notice of the information relevant for the assessment of the taxpayer’s request to form a fiscal unity;

(ii) the taxpayer on that basis could derive expectations from the decree that the tax inspector took the position that the conditions for a fiscal unity were met; and

(iii) that position was not so obvious contrary to a proper application of the law that the taxpayer should reasonably have realized its incorrectness.

The taxpayer’s appeal on the decision must be rejected if the taxpayer has provided incorrect or incomplete information with its application or has withheld correct and complete information from the tax inspector where the taxpayer in all reasonableness should have known that the inspector was therefore unable to properly assess the application.

According to the Advocate General, this means that the Secretary of State's appeal in cassation is well-founded and the case must be referred for investigation and assessment of the facts of the case in the light of the correct yardstick of the legal expectation doctrine instead of the bad faith doctrine as used by the Court of Appeal.

The full text of the opinion of the Advocate General can be found here (only available in the Dutch language).

Copyright – internationaltaxplaza.info