On October 13, 2022 on the website of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) a very interesting judgment of the Court of Justice of the European Union (the CJEU) in Case C-431/21, X GmbH & Co. KG versus Finanzamt Bremen, ECLI:EU:C:2022:792, was published. The case regards the obligation to keep transfer pricing documentation and the possibility to impose a surcharge/penalty if the taxpayer fails to comply with the obligation to keep such documentation and/or to provide such documentation to the tax authorities.

Introduction

This request for a preliminary ruling concerns the interpretation of Articles 43 and 49 EC and of Articles 49 and 56 TFEU.

The request has been made in proceedings between X GmbH Co. KG and the Finanzamt Bremen (Tax Office, Bremen, Germany) concerning a surcharge on the taxable income applied by the latter (‘the tax surcharge’) for failure to comply with the tax obligation to keep documents concerning cross-border business relations between related companies.

The dispute in the main proceedings and the question referred for a preliminary ruling

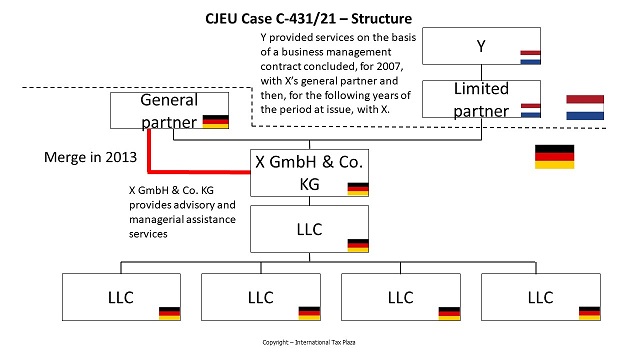

6 X, the applicant in the main proceedings, is a limited partnership, established in Bremen (Germany), which holds and manages shareholdings and provides advisory and managerial assistance services. At the time of the facts in the main proceedings, it held all the shares in a limited liability company having its registered office in Germany, which itself held all the shares in four other limited liability companies having their registered offices in that Member State.

7 X’s general partner is a company established in Germany and its limited partner is a company established in the Netherlands, whose sole shareholder, Y, is also a company established in the Netherlands.

8 In 2013, X and the company which was the general partner merged.

9 Y provided services on the basis of a business management contract concluded, for 2007, with X’s general partner and then, for the following years of the period at issue, with X.

10 That contract provides that Y’s remuneration is to take into account the costs and expenses actually incurred, with the exception of Y’s shareholder’s costs (‘the reimbursable costs’).

11 Y is required to establish documents concerning the reimbursable costs and a detailed annual account. It is apparent from the order for reference that Y did not, however, provide such an account.

12 X was the subject of a tax audit for the tax years 2007 to 2010 relating, in particular, to the management fees paid to Y. The documentation that X was invited to provide under the obligation set out in Paragraph 90(3) of the Tax Code (‘the obligation to provide fiscal documentation’) was held to be insufficient by the German tax authorities.

13 On 7 January 2016, the Netherlands tax authorities, at X’s request, informed the German tax authorities that Y had invoiced X for all its costs, including costs which were not reimbursable costs.

14 On 17 March 2016, X and the German tax authorities entered into a transaction with the participation of Y in which it was agreed that part of X’s payments to Y during the period at issue, amounting to EUR 400 000 per year and for a total amount of EUR 1.6 million, had been incorrectly entered in the accounts as operating expenses.

15 In their report of 10 June 2016, the German tax authorities stated that the documents submitted by X in respect of the obligation to provide fiscal documentation were unusable.

16 Consequently, on 8 November 2016, those authorities ordered X to pay a tax surcharge, corresponding to 5% of X’s additional income, estimated by those authorities at EUR 20 000 per year, making a total amount of EUR 80 000.

17 On 9 December 2016, X lodged a complaint against that decision with those authorities, which rejected it.

18 On 27 December 2017, X brought an action against that decision before the Finanzgericht Bremen (Finance Court, Bremen, Germany), in which it claimed that Paragraph 162(4) of the Tax Code, on the basis of which the tax surcharge was imposed on it, infringed the freedom of establishment.

19 The Finanzgericht Bremen (Finance Court, Bremen) states that the Bundesfinanzhof (Federal Finance Court, Germany) has held that the obligation to provide fiscal documentation constitutes a restriction on the freedom of establishment which may be regarded as justified by overriding reasons in the public interest and, in particular, by the need to ensure the preservation of the allocation of powers of taxation between the Member States and to allow effective fiscal inspection, but has not ruled on the compatibility with EU law of the tax surcharge that may be imposed in the event of an infringement of that obligation. According to the referring court, that surcharge may go beyond what is necessary to achieve those objectives.

20 In those circumstances, the Finanzgericht Bremen (Finance Court, Bremen) decided to stay the proceedings and to refer the following question to the Court of Justice for a preliminary ruling:

‘Must Article 43 EC and Article 49 TFEU, which guarantee the freedom of establishment (or, respectively, Article 49 EC and Article 56 TFEU, which guarantee the freedom to provide services), be interpreted as precluding national legislation under which, in situations involving transactions with a foreign element, the taxpayer must keep records on the nature and content of his, her or its business relations with related parties, including the economic and legal bases for an arm’s-length agreement on prices and other terms and conditions with the related parties, and under which, where the taxpayer fails to submit those records when requested to do so by the tax authority, or where the records submitted are fundamentally unusable, not only is there a rebuttable presumption that his, her or its income subject to tax domestically, which such records serve to determine, is higher than the income that he, she or it has declared, and, if in such cases the tax authority is required to make an estimate and such income can be determined only within a certain range, in particular only on the basis of price bands, the upper value of that range may be taken as the basis to the detriment of the taxpayer, but, in addition, a surcharge is to be imposed which is at least 5% and at most 10% of the excess income determined, but not less than EUR 5 000, and which, in the event that usable records are submitted late, is up to EUR 1 000 000, but not less than EUR 100 for each full day of delay, whereby the imposition of a surcharge is to be waived only if the non-compliance with the record-keeping obligations appears to be excusable or if any fault involved is only minor?’

Judgment

The Court (Ninth Chamber) ruled as follows:

Article 49 TFEU must be interpreted as meaning that it does not preclude national legislation under which, in the first place, the taxpayer is subject to an obligation to provide documentation on the nature and content of, as well as on the economic and legal bases for, prices and other terms and conditions of his, her or its cross-border business transactions, with parties with which he, she or it has a relationship of interdependence, in capital or other aspects, enabling that taxpayer or those parties to exercise a definite influence over the other, and which provides, in the second place, in the event of infringement of that obligation, not only that his, her or its taxable income in the Member State concerned is rebuttably presumed to be higher than that which has been declared, and the tax authorities may carry out an estimate to the detriment of the taxpayer, but also that a surcharge of an amount equivalent to at least 5% and at most 10% of the excess income determined is imposed, with a minimum amount of EUR 5 000, unless non-compliance with that obligation is excusable or if the fault involved is minor.

Legal context

3 Paragraph 90, concerning the obligations of cooperation imposed on taxable persons, of the Abgabenordnung (the German Tax Code) (BGBl. 2002 I, p. 3866), in its version applicable to the dispute in the main proceedings (‘the Tax Code’), provides:

‘(1) The parties concerned shall be obliged to cooperate in establishing the facts. They shall comply, in particular, with their obligation to cooperate by duly revealing all the facts relevant to the imposition of tax and by communicating the evidence which is known to them. The extent of those obligations shall depend on the circumstances of the case.

…

(3) In situations involving transactions with a foreign element, the taxpayer shall keep records of the nature and content of his, her or its business relations with related parties within the meaning of Paragraph 1(2) of the Außensteuergesetz [Gesetz über die Besteuerung bei Auslandsbeziehungen (Law on taxation in international contexts) of 8 September 1972 (BGBl. 1972 I, p. 1713)]. The record-keeping obligation shall also cover the economic and legal bases for an arm’s-length agreement on prices and other terms and conditions with related parties. In the case of exceptional business transactions, records must be compiled in a timely manner. The record-keeping obligations shall apply by analogy to taxpayers who are required, for the purposes of taxation at national level, to allocate profits between their national undertaking and its foreign establishments or to determine the profits of the national establishments of their foreign undertaking. In order to ensure uniform application of the law, the Federal Ministry of Finance shall be authorised to define by implementing decree, with the consent of the Bundesrat, the nature, content and scope of the records to be kept. As a general rule, the tax authority may require the submission of records only for the purpose of conducting a tax audit. The submission is based on Paragraph 97, provided that subparagraph 2 of that provision does not apply. The submission must be made upon request within 60 days. In so far as the submission concerns records relating to exceptional business transactions, the time limit shall be 30 days. In duly justified special cases, the time limit for submission may be extended.’

4 Paragraph 162 of the Tax Code, entitled ‘Estimating tax bases’, provides:

‘(1) Where the tax authority is unable to determine or calculate the tax base, it shall be required to make an estimate. It shall take account of all the relevant circumstances for that estimate.

…

(3) If a taxpayer infringes his, her or its obligations to cooperate under Paragraph 90(3) by failing to submit records, or if the records submitted are fundamentally unusable, or if it is determined that the taxpayer has not compiled the records as described in the third sentence of Paragraph 90(3) in a timely manner, there shall be a rebuttable presumption that his, her or its taxable income in Germany, which the records described in Paragraph 90(3) serve to determine, is higher than the income which he, she or it has declared. If in such cases the tax authority is required to conduct an estimate and that income can be determined only within a certain estimated range, in particular solely on the basis of price bands, the upper value of that range may be taken as the basis to the detriment of the taxpayer. If, despite the submission of usable records by the taxpayer, there are indications that application of the arm’s-length principle would cause the taxpayer’s income to be higher than the income declared on the basis of the records, and if corresponding doubts to that effect cannot be dispelled because a foreign related party fails to fulfil its obligations to cooperate laid down in Paragraph 90(2) or its obligation to provide information referred to in Paragraph 93(1), the second sentence shall be applied by analogy.

(4) If a taxpayer fails to submit records as described in Paragraph 90(3) or if the records submitted are essentially unusable, a surcharge of EUR 5 000 shall be imposed. The surcharge shall be at least 5% and at most 10% of the excess income resulting from the correction made pursuant to subparagraph 3 where, as a result of that correction, the surcharge exceeds EUR 5 000. In cases where usable records are submitted late, the maximum amount of the surcharge shall be EUR 1 000 000, with, however, at least EUR 100 for each full day following expiration of the deadline. In so far as the tax authorities are given discretion with regard to the amount of the surcharge, account must be taken, not only of the objective of that surcharge, which is to ensure that the taxpayer complies with the obligation to compile and submit, within the time limits, the records as described in Paragraph 90(3), in particular the benefits derived by the taxpayer, but also, in the event of late submission, of the duration of the failure to comply with the time limit. A surcharge shall not be fixed if the failure to comply with the record-keeping obligations referred to in Paragraph 90(3) appears to be excusable or if the fault is only minor. Fault committed by a legal representative or an employee shall amount to personal fault. The surcharge must, as a general rule, be fixed after completion of the tax audit.’

5 Paragraph 1(2) of the Law on taxation in international contexts, in its version applicable to the dispute in the main proceedings, provides:

‘A party is related to a taxpayer if:

- the party has a direct or indirect shareholding in that taxpayer of at least 25% (substantial shareholding) or can exercise direct or indirect influence over the taxpayer or, conversely, where the taxpayer has a substantial shareholding in that party or can exercise direct or indirect influence over that party; or

- a third party has a substantial shareholding in that party or taxpayer, or can exercise direct or indirect influence over the party or the taxpayer; or

- the party or the taxpayer is in a position, when agreeing the terms of a business relationship, to exercise an influence over the other which has its source outside that business relationship or if one of those parties has a particular interest in the other’s generation of income.’

Consideration of the question referred

Preliminary observations

21 As a preliminary point, it should be noted that it is apparent from the actual wording of the order for reference and from the wording of the question referred that it is necessary to provide guidance on the interpretation of EU law which will enable the referring court to assess the compatibility with EU law not only of the tax surcharge penalising failure to comply with the obligation to provide fiscal documentation, but also of that obligation itself.

22 By contrast, it does not appear necessary, for the purposes of the dispute in the main proceedings, to provide the referring court with answers enabling it to assess the compatibility with EU law of the aspects of the German legislation referred to by that court relating to the tax surcharge applicable in the event that the applicable fiscal documentation is submitted late.

Applicable freedom of movement

23 It should be noted that, although the question referred for a preliminary ruling concerns the provisions of the EC and FEU Treaties on the freedom of establishment and the freedom to provide services, it is necessary to determine the freedom applicable in the main proceedings.

24 In that regard, according to established case‑law, in order to determine whether national legislation comes within the scope of one or other of the freedoms of movement, the purpose of the legislation concerned must be taken into consideration (judgment of 21 January 2010, SGI, C‑311/08, EU:C:2010:26, paragraph 25 and the case-law cited).

25 Furthermore, national legislation intended to apply only to those shareholdings which enable the holder to exert a definite influence on a company’s decisions and to determine its activities come within the scope of freedom of establishment (judgment of 31 May 2018, Hornbach-Baumarkt, C‑382/16, EU:C:2018:366, paragraph 28 and the case-law cited).

26 In this respect, it should be noted that the obligation to provide fiscal documentation concerns only cross-border business transactions between ‘related’ undertakings within the meaning of national law, that link being defined by the existence of a relationship of interdependence, in capital or other aspects, which, it appears in each case, characterises a definite influence of one over the other. That is in any event the case where that relation is defined by the fact, which is the situation in the main proceedings, that a party has a shareholding corresponding directly or indirectly to at least one quarter of the taxpayer’s capital. Y indirectly holds, through a company established in the Netherlands, 100% of the capital of X, established in Germany.

27 In the light of the foregoing, it is necessary to examine the national legislation at issue exclusively in the light of the freedom of establishment.

28 Moreover, although the referring court has referred, in its question, to the freedom of establishment enshrined in Articles 43 EC and 49 TFEU, respectively, reference will be made only to Article 49 TFEU, the interpretation, in any event, also being applicable to Article 43 EC.

29 Consequently, the view must be taken that, by its question, the referring court asks, in essence, whether Article 49 TFEU must be interpreted as precluding legislation under which, in the first place, the taxpayer is subject to an obligation to provide documentation on the nature and content of, as well as on the economic and legal bases for, the prices and other terms and conditions of his, her or its cross-border business transactions, with parties with which he, she or it has a relationship of interdependence, in capital or other aspects, enabling that taxpayer or those parties to exercise a definite influence over the other and which provides, in the second place, in case of infringement of that obligation, not only that his, her or its taxable income in the Member State concerned is rebuttably presumed to be higher than that which has been declared, and the tax authorities may carry out an estimate to the detriment of the taxpayer, but also that a surcharge of an amount equivalent to at least 5% and at most 10% of the excess income determined is imposed, with a minimum amount of EUR 5000, unless non-compliance with that obligation is excusable or if the fault involved is minor.

Whether there is a restriction on the freedom of establishment

The obligation to submit a tax declaration

30 According to settled case-law, freedom of establishment, conferred on EU nationals by Article 49 TFEU, entails, according to Article 54 TFEU, for companies or firms formed in accordance with the law of a Member State and having their registered office, central administration or principal place of business within the European Union, the right to exercise their activity in another Member State through a subsidiary, branch or agency (judgment of 8 October 2020, Impresa Pizzarotti (Unusual advantage granted to a non-resident company), C‑558/19, EU:C:2020:806, paragraph 21 and the case-law cited).

31 The Court has in particular held that a restriction on freedom of establishment arises in the case of national legislation under which unusual or gratuitous advantages granted by a resident company to a company with which it has a relation of interdependence are added to the former company’s own profits only if the recipient company is established in another Member State (judgment of 8 October 2020, Impresa Pizzarotti (Unusual advantage granted to a non-resident company), C‑558/19, EU:C:2020:806, paragraph 24 and the case-law cited).

32 In the present case, the obligation to provide fiscal documentation covers cross-border business transactions carried out between a resident company and another company with which it has a relationship of interdependence, in capital or other aspects, enabling the latter to exert a definite influence over the resident company. It is also apparent from the file submitted to the Court that resident companies are not subject to a comparable obligation in respect of business transactions concluded with resident companies.

33 Such a difference in treatment is liable to constitute a restriction on freedom of establishment, within the meaning of Article 49 TFEU, since companies established in the State of taxation enjoy less favourable treatment in the case where the companies with which they have a relationship of interdependence are established in another Member State.

34 A parent company, established in another Member State, might thereby be deterred from acquiring, creating or maintaining a branch in that first Member State (see, by analogy, judgment of 8 October 2020, Impresa Pizzarotti (Unusual advantage granted to a non-resident company), C‑558/19, EU:C:2020:806, paragraph 27 and the case-law cited).

35 According to settled case-law, a tax measure which is liable to hinder the freedom of establishment is permissible only if it relates to situations which are not objectively comparable or if it can be justified by overriding reasons in the public interest recognised by EU law. It is further necessary, in such a case, that it is appropriate for ensuring the attainment of the objective in question and does not go beyond what is necessary to attain that objective (judgment of 8 October 2020, Impresa Pizzarotti (Unusual advantage granted to a non-resident company), C‑558/19, EU:C:2020:806, paragraph 28 and the case-law cited).

36 In that regard, it follows from settled case-law that the comparability of a cross-border situation with an internal situation within a Member State must be examined having regard to the aim pursued by the national provisions at issue as well as to the purpose and content of those provisions (judgment of 7 April 2022, Veronsaajien oikeudenvalvontayksikkö (Exemption of contractual investment funds), C‑342/20, EU:C:2022:276, paragraph 69).

37 However, the German Government essentially puts forward arguments relating to the need to guarantee the effectiveness of fiscal inspection of transfer pricing in order to determine whether the taxpayer’s cross-border transactions with related undertakings are compatible with market conditions, which relate less to the question of the comparability of situations than to that of the justification based on the need to guarantee the effectiveness of fiscal inspection in order to preserve the balanced allocation of the power of taxation between the Member States (see, by analogy, judgment of 31 May 2018, Hornbach-Baumarkt, C‑382/16, EU:C:2018:366, paragraph 40).

38 It follows from the file submitted to the Court that such legislation, by simplifying fiscal inspection, pursues the objective of ensuring the balanced allocation of the power of taxation between Member States, which constitutes, as is apparent from the case-law of the Court, an overriding reason in the public interest (see, to that effect, judgments of 12 July 2012, Commission v Spain, C‑269/09, EU:C:2012:439, paragraph 63, and of 8 October 2020, Impresa Pizzarotti (Unusual advantage granted to a non-resident company), C‑558/19, EU:C:2020:806, paragraph 31).

39 The need to maintain a balanced allocation of the power of taxation between the Member States may be capable of justifying a difference in treatment where the system in question is designed to prevent conduct liable to jeopardise the right of a Member State to exercise its power of taxation in relation to activities carried out within its territory (judgment of 31 May 2018, Hornbach-Baumarkt, C‑382/16, EU:C:2018:366, paragraph 43).

40 In that regard, the Court has already held that permitting subsidiaries of non-resident companies to transfer their profits in the form of unusual advantages to their parent companies may well undermine the balanced allocation of the power of taxation between Member States and that it would be liable to undermine the very system of the allocation of the power of taxation between the Member States, because the Member State of the subsidiary granting such advantages would be forced to renounce its right, in its capacity as the State of residence of that subsidiary, to tax that subsidiary’s income in favour, possibly, of the Member State in which the recipient parent company has its registered office (see, to that effect, judgment of 8 October 2020, Impresa Pizzarotti (Unusual advantage granted to a non-resident company), C‑558/19, EU:C:2020:806, paragraph 32 and the case-law cited).

41 Consequently, by requiring the taxpayer, in this case the subsidiary resident in the Member State of taxation, to provide documentation relating to his, her or its cross-border business transactions with undertakings with which he, she or it has a relationship of interdependence and concerning both the nature and conditions of those transactions and the economic and legal bases for agreements on prices and other terms and conditions, the obligation to provide fiscal documentation enables that Member State to monitor more effectively and with greater precision whether those transactions were concluded in accordance with market conditions and to exercise its power of taxation in relation to activities carried out within its territory (see, by analogy, judgment of 8 October 2020, Impresa Pizzarotti (Unusual advantage granted to a non-resident company), C‑558/19, EU:C:2020:806, paragraph 33).

42 Therefore, national legislation such as that providing for the obligation to furnish fiscal documentation, which ensures that a taxpayer’s fiscal inspection is more effective and precise, and which seeks to prevent profits generated in the Member State concerned from being transferred outside the tax jurisdiction of that Member State by means of transactions that are not in accordance with market conditions, without being taxed, is appropriate for ensuring the preservation of the allocation of the power of taxation between Member States (see, by analogy, judgment of 8 October 2020, Impresa Pizzarotti (Unusual advantage granted to a non-resident company), C‑558/19, EU:C:2020:806, paragraph 34).

43 Nevertheless, it is important that such legislation does not go beyond what is necessary to attain the objective pursued.

44 That will be the case if the taxpayer is given an opportunity, without being subject to undue administrative constraints, to produce relevant evidence relating to cross-border business transactions with undertakings with which the taxpayer has a relationship of interdependence (see, by analogy, judgment of 8 October 2020, Impresa Pizzarotti (Unusual advantage granted to a non-resident company), C‑558/19, EU:C:2020:806, paragraph 36).

45 In the present case, it is apparent from the very wording of the question referred that the obligation to provide fiscal documentation concerns ‘the nature and content’ of business relations, but also ‘the economic and legal bases for an … agreement on prices and other terms and conditions’. Paragraph 90(3) of the Tax Code states, however, that the nature, content and scope of the records to be kept must be specified by an implementing decree the content of which is not specified in the order for reference and with regard to which it is for the referring court to determine whether it is not such as to give rise to excessive administrative constraints for the taxpayer.

46 It is also apparent from the order for reference that the tax authority should, as a general rule, require those documents to be submitted only in order to carry out a fiscal inspection and that, in principle, such submission is to take place within 60 days, a period which may, in duly justified cases, be extended.

47 Consequently, subject to the verifications to be made in that regard by the referring court, it does not appear that such an obligation to provide fiscal documentation goes beyond what is necessary to attain the objective pursued.

48 It follows that Article 49 TFEU does not, in principle, preclude such an obligation.

The tax surcharge

49 With regard to the tax surcharge, which penalises failure to comply with the obligation to provide fiscal documentation, it should be noted that, although systems of penalties in the field of taxation come within the powers of the Member States in the absence of harmonisation at EU level, such systems should not have the effect of jeopardising the freedoms provided for by the FEU Treaty (see, to that effect, judgment of 3 March 2020, Google Ireland, C‑482/18, EU:C:2020:141, paragraph 37 and the case-law cited).

50 In the present case, since the tax surcharge penalises failure to comply with the obligation to provide fiscal documentation, which is capable of constituting a restriction on freedom of establishment, that surcharge is itself capable of constituting such a restriction.

51 However, as has been pointed out in paragraph 35 of the present judgment, such a restriction may be permissible if it is justified by overriding reasons in the public interest and in so far as, in such a case, its application is appropriate for securing the attainment of the objective pursued and does not go beyond what is necessary in order to attain it.

52 The Court has also held that the imposition of penalties, including criminal penalties, may be considered to be necessary in order to ensure compliance with national rules, subject, however, to the condition that the nature and amount of the penalty imposed is, in each individual case, proportionate to the gravity of the infringement which it is designed to penalise (judgment of 3 March 2020, Google Ireland, C‑482/18, EU:C:2020:141, paragraph 47 and the case-law cited).

53 As regards the question whether the tax surcharge is appropriate for securing the objective pursued by the national legislature, it should be noted that the application of a surcharge of a sufficiently high amount appears capable of deterring taxpayers subject to the obligation to provide fiscal documentation from disregarding that obligation and, thus, of preventing the Member State of taxation being deprived of the possibility of monitoring cross-border transactions effectively between companies with a relationship of interdependence in order to ensure a balanced allocation of the power of taxation between the Member States.

54 The argument put forward by the applicant in the main proceedings and by the European Commission that such a surcharge may not be necessary if there are already applicable, less severe penalties in comparable national situations appears, in actual fact, to refer more to the appropriateness of the amount of the tax surcharge. In any event, it should be noted that the existence of such penalties is not apparent from the file before the Court. Furthermore, it should be noted that the fact that German legislation allegedly provides for less severe penalties in the case where the taxpayer fails, in purely internal situations, to comply with the obligations of cooperation in the context of combating tax avoidance and unfair tax competition is a priori irrelevant for the purpose of assessing the necessity of the tax surcharge, which pursues a different objective, namely that of preserving the balanced allocation of the power of taxation between the Member States.

55 As regards the proportionality of that surcharge, it must be held that the imposition of a penalty equal to at least 5% and at most 10% of the excess income resulting from the correction made by the tax authorities in the event of infringement of the obligation to provide fiscal documentation, without limitation of the absolute maximum amount, and with a minimum amount of EUR 5 000, including where no excess income has ultimately been established by the tax authorities, does not appear, in itself, to be liable to lead to the imposition of a disproportionate penalty amount.

56 As the Commission states, the setting of the amount of that penalty according to a percentage of the adjustment of taxable income makes it possible to establish a correlation between the amount of the fine and the seriousness of the failure to fulfil obligations. Providing for a minimum penalty of EUR 5 000 also makes it possible to preserve the deterrent effect of the tax surcharge where its minimum amount is too low, while setting a ceiling of 10% ensures that the amount of that surcharge is not excessive.

57 That analysis is supported by the fact that the tax surcharge is not applicable if the infringement of the obligation to provide fiscal documentation is excusable or if the fault is only minor.

58 Finally, the fact that the German legislation also provides, in the event of infringement of the obligation to submit a tax declaration, for the adjustment of the taxable income of the taxpayer, which is then rebuttably presumed to be underestimated, cannot justify a different interpretation.

59 Those rules are different in nature from that of the tax surcharge, since they are not intended to penalise failure to comply with the obligation to provide fiscal documentation but rather to correct the amount of the taxpayer’s taxable income.

60 Consequently, Article 49 TFEU must be interpreted as meaning that it also does not preclude a tax surcharge such as that at issue in the main proceedings.

61 In the light of the foregoing, the answer to the question referred is that Article 49 TFEU must be interpreted as not precluding national legislation under which, in the first place, the taxpayer is subject to an obligation to provide documentation on the nature and content of, as well as on the economic and legal bases for, prices and other terms and conditions of his, her or its cross-border business transactions, with parties with which he, she or it has a relationship of interdependence, in capital or other aspects, enabling that taxpayer or those parties to exercise a definite influence over the other, and which provides, in the second place, in the event of infringement of that obligation, not only that his, her or its taxable income in the Member State concerned is rebuttably presumed to be higher than that which has been declared, and the tax authorities may carry out an estimate to the detriment of the taxpayer, but also that a surcharge of an amount equivalent to at least 5% and at most 10% of the excess income determined is imposed, with a minimum amount of EUR 5 000, unless non-compliance with that obligation is excusable or if the fault involved is minor.

Costs

62 Since these proceedings are, for the parties to the main proceedings, a step in the action pending before the national court, the decision on costs is a matter for that court. Costs incurred in submitting observations to the Court, other than the costs of those parties, are not recoverable.

Copyright – internationaltaxplaza.info

Follow International Tax Plaza on Twitter (@IntTaxPlaza)