On January 21, 2022 on the website of the Dutch courts a conclusion of the Dutch Advocate General with respect to the Dutch liquidation loss scheme was published. The conclusion was delivered in case number: 21/02980 (ECLI:NL:PHR:2021:1189).

Introduction

The Dutch participation exemption arranges that profits and losses that a shareholder realizes/incurs through/from a qualifying shareholding in a subsidiary are exempt/non-deductible for Dutch corporate income tax purposes. The general thought behind the participation exemption is to avoid that the same taxable profit (or loss) is being taxed (deducted/settled) twice. However, for situations in which a subsidiary is being liquidated the Dutch corporate income tax Act contains a liquidation loss scheme. The liquidation loss scheme arranges that the losses incurred by that subsidiary that were not settled with taxable profits disappear and are no longer available for settlement/deduction within the group. The liquidation loss scheme arranges that under conditions Dutch shareholders are allowed to deduct a liquidation loss which it incurs when a qualifying subsidiary is liquidated. In principle a liquidation loss is calculated in accordance with the following formula: liquidation loss = amount sacrificed -/- liquidation proceeds.

In the underlying case the question arises how the amount sacrificed for a subsidiary is to be determined when the status of a public enterprise changes from being not-liable for Dutch corporate income tax purposes, to being liable for Dutch corporate income tax purposes because of an Act coming into effect.

Facts

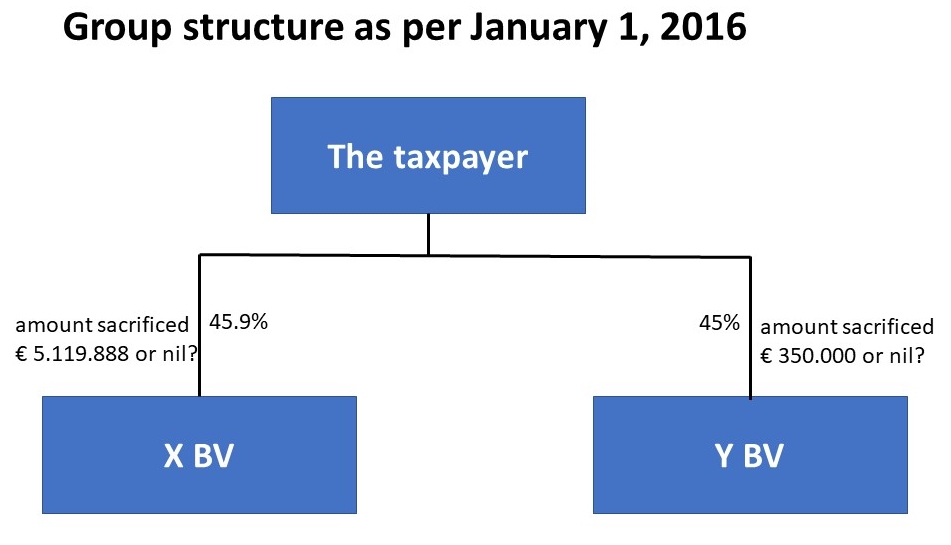

The taxpayer in the underlying case is a regional development company with the aim of stimulating economic activity in the Northern part of the Netherlands. On January 1, 2016 the taxpayer became liable for the Dutch corporate income tax due to the entering into force of the Wet modernisering vennootschapsbelastingplicht overheidsondernemingen (WmVpbO) (the Act modernization of the corporate income tax liability public enterprises).

On January 1, 2016 the taxpayer owned 45.9% of the shares in X BV and 45% of the shares in Y BV. The historic cost prices of the shareholdings in these shareholdings amount to respectively € 5.119.888 en € 350.000. In 2016, after becoming liable for Dutch corporate income tax, the taxpayer liquidated these 2 subsidiaries. No liquidation payments have been made and the activities have not been continued by the claimant or any of its related party.

The taxpayer filed a corporate income tax return in which it reported a negative taxable income of € 4.680.959. In the tax return 2 liquidation losses as meant in Article 13d of the Dutch corporate income tax Act were included. These liquidation losses totaled to € 5.469.888. It regards a loss of € 350.000 relating to the shareholding in Y BV and a loss of € 5.119.888 relating to the shareholding in X BV.

Parties (taxpayer and tax authorities) are disputing how the amounts sacrificed for the subsidiaries have to be determined. The tax authorities are of the opinion that the amounts sacrificed are to be set at the fair value of the shareholdings in the subsidiaries on January 1, 2016 (nill), which is the moment that the taxpayer became liable for Dutch corporate income tax. The taxpayer is of the opinion that the amounts sacrificed are to be set at the historical cost prices of the subsidiaries.

The District Court ruled in favor of the taxpayer. It based its judgment on the (literal) text of the law and the lack of transitional regulations. The District Court therefore ruled that the immediate effect of the WmVpbO must be assumed. The District Court ruled that no reference can be found in the legislative history for the position that the intended liquidation loss deduction would violate the purpose and purport of the liquidation loss scheme as included in the Dutch corporate income tax Act and that therefore a derogation from Article 13d Dutch corporate income tax Act should be made. The Inspector desires a regulatory compartmentalization and, according to the District Court, that is not up to a judge; given HR BNB 2013/177 arranging transitional regulations is up to the legislator.

In its appeal for cassation the Secretary of State pleas that the liquidation losses are not to be included in the taxpayer’s total profit because they arose outside (before) the taxpayer’s tax liability (period). According to the Secretary of State on January 1, 2016 all of the taxpayer’s assets and liabilities, except for certain goodwill (HR BNB 1991/90 and HR BNB 2007/81), had to be stated at their fair value at the balance sheet for tax purposes. Therefore to his opinion the amounts sacrificed cannot exceed the fair value of the shareholding in the subsidiaries at that time.

From the analysis of the Advocate General

According to the Advocate General the normal valuation rules do not seem relevant in the underlying case, since according to the legislator the amount sacrificed is not an (opening) balance sheet item, but an off-balance item that is (thus) determined outside the normal valuation and profit & loss determination rules. Furthermore according to the Advocate General the liquidation loss scheme is a rough and improperly allocated (allocation to the shareholder) compensation for losses incurred by the subsidiary. Reflections on the concept of total profit (either at the level of the subsidiary or at the level of the parent) seem then of little relevance. The legislator has explicitly refrained from transferring the subsidiary’s losses as determined in accordance with the normal regulations as too complicated; the legislator only wanted to approach those losses 'roughly' and to take an off-balance amount into account at the level of the parent entity. In such a systemic strange scheme, systematical arguments are useless.

According the Advocate General the argument that it first must be determined whether the taxpayer actually realized a total profit before an objective exemption of any part of that profit can be claimed does therefore not hold water. After all, the liquidation loss scheme is an exception to the objective exemption that a parent company gets for the results it realizes on/through its participations. This exception however, does not revert back to the normal way in which the profit of a parent company is determined, but it is an exception which covers the loss (determined in accordance with the normal profit determination rules) incurred by the subsidiary at the level of parent company in a lump sum manner and outside of the normal regulations.

In contrast to the case HR BNB 2013/177, in this case during the parliamentary discussion of the relevant amendment to the law the legislator did not say anything about whether or not transitional regulations were desired with respect to the application of the (liquidation loss scheme of the) participation regime, but from HR BNB 2013/177 it follows that in the absence of statutory transitional law/regulations, the Dutch Supreme Court assumes immediate effect of legislative changes.

Also different as in HR BNB 2013/177, this case does not concern a change in the participation exemption itself, but a change in the tax liability of public enterprises. The Advocate General however does not see why that would make any difference to the starting point that the court cannot provide for transitional regulations omitted by the legislator.

The Secretary of State considers it logical that the legislator did not draft any specific transitional provisions because the normal rules for drawing up an opening balance for tax purposes would also apply to determine the amount sacrificed, which means the participations are to be values at fair value. However, the Advocate General is of the opinion that that is not logical, now that the legislator did not want those ordinary valuation and profit determination rules to apply to the liquidation loss scheme, which takes place in an off-balance manner.

Although the transitional problem in the underlying case is clearer than in HR BNB 2013/177, the judge is in the dark about what the legislator would have done if he would have considered the amount sacrificed for participations of public companies that become liable to tax (which cannot be deduced from an opening balance sheet). The liquidation loss scheme is undogmatic and systematically aimed at simplicity. On the one hand the scheme wants to recoup the evaporating losses of the liquidated subsidiary, but on the other hand, because of that simplicity, it ties in with a loss (determined off-balance) that manifests itself at the level of the parent company. The Advocate General does not see how the judge should deduce from the aforementioned what the legislator would have intended, if he had intended anything.

Therefore the Advocate General sees no reason to deviate from the text of the law and from HR BNB 2013/177. The Advocate General proposes that the Dutch Supreme Court declares the State Secretary's appeal in cassation unfounded.

You can find the whole text of the conclusion (in the Dutch language) here.

Copyright – internationaltaxplaza.info